(This post continues a series where I share readings that I’ve found useful or, at the very least, intellectually stimulating. See here and here.)

Salam/Namaskar

The nineteenth century was somewhat a moment for international law. It was marked by a distinctive, I’d say, thought style in which organising international congresses to address perceived “social problems” became almost a thing. Intellectual property (IP) treaties were no exception. The late nineteenth century, as Bentley and Sherman claim, was a period of consolidation of IP laws and the beginnings of IP expertise as a specialised legal field. (Its a must-read book for IP history enthusiasts!)

I recently chanced upon two pieces that speak nicely to this broader historical moment, and I think our readers here may find them both useful and intriguing. Before pasting their abstracts below, let me briefly flag what they offer.

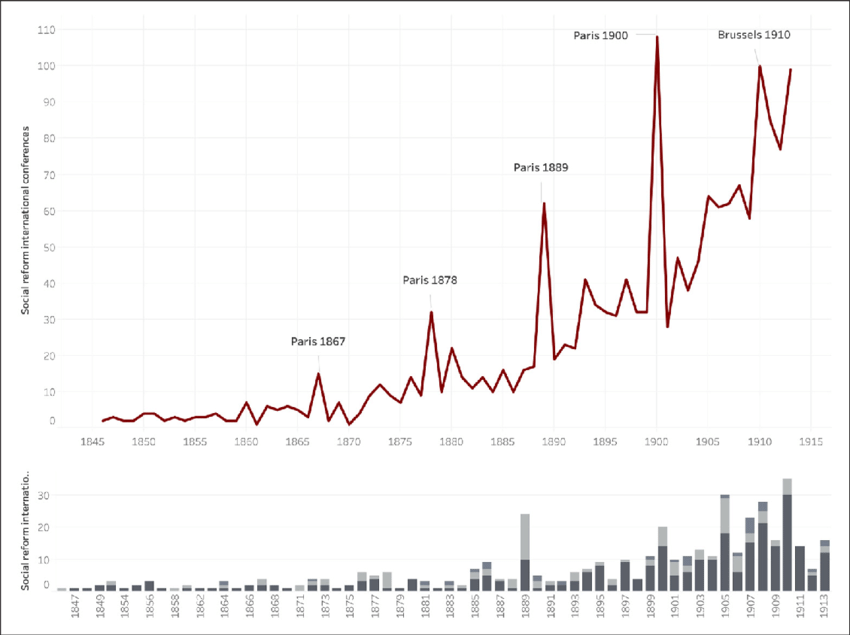

The first piece looks at the international congresses held between 1846 and 1914. ‘Tis a short yet sharp account of the early conference culture of internationalism—mapping not only the sheer proliferation of such meetings, but also the kinds of ideas, aspirations, and even anxieties that circulated within them. It can be a useful piece for someone willing to dig deeper into this topic. For those interested in IP like me, this can turn useful in tracing the genealogy of international copyright law.

Belgium, as is well known, emerges as a key site in this history. Brussels hosted a remarkable number of international copyright meetings, most notably the 1858 Congress, arguably the first serious attempt to forge the foundation of international copyright law, which would later become the Berne Convention. The second piece offers why Belgium came to organise so many international congresses in the first place. These congresses functioned as a form of soft power.

Read together, these pieces help situate international copyright law not merely as a doctrinal or treaty-based development, but as part of a wider nineteenth-century culture of conferencing, expertise-building, and international problem-solving—one where law, politics, and power were deeply intertwined.

Okay, here are the readings:

Christophe Verbruggen et al, Social Reform International Congresses and Organizations (1846–1914): From Sources to Data, Journal of Open Humanities Data (2022)

TIC-Collaborative was a collaborative digital humanities project that focused on transnational intellectual cooperation (TIC) in the long nineteenth century, in particular on transnational connections in the field of social reform. The dataset contains information on over 1650 international congresses and 450 organizations and conference series related to the social question. The project focussed on the Low Countries and a selection of reform areas.

The piece also provides a gripping graph showing how the congresses escalated after 1845, see page 4

DAVID AUBIN, Congress Mania in Brussels, 1846—1856: Soft Power, Transnational Experts, and Diplomatic Practices, 50(4) Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences (2020) pp. 340-363 (24 pages)

In 1853, the director of the Belgium Royal Observatory, Adolphe Quetelet, welcomed delegates from several countries to two consecutive meetings that have acquired considerable reputation as the first international congresses of, respectively, mete- orology and statistics. This paper examines the local context where several similar international congresses (on free trade, universal peace, prison reform, public hygiene, etc.) were organized in the same decade. It argues that the new Belgian state developed this new form of international conference in order to bolster its soft power in the Concert of Nations. It also discusses tensions between national interests and global beliefs in the efficiency of science, which arose from these congresses.

On a tangential (but highly recommended) note, do check out this beautifully penned piece by my dearest friend Shivam Kaushik, How India Learnt to Stop Complaining and Love Copyright. It pairs rather well with the themes discussed here.

Okay, that’s it for this post! See you in the next post.