Bonjour,

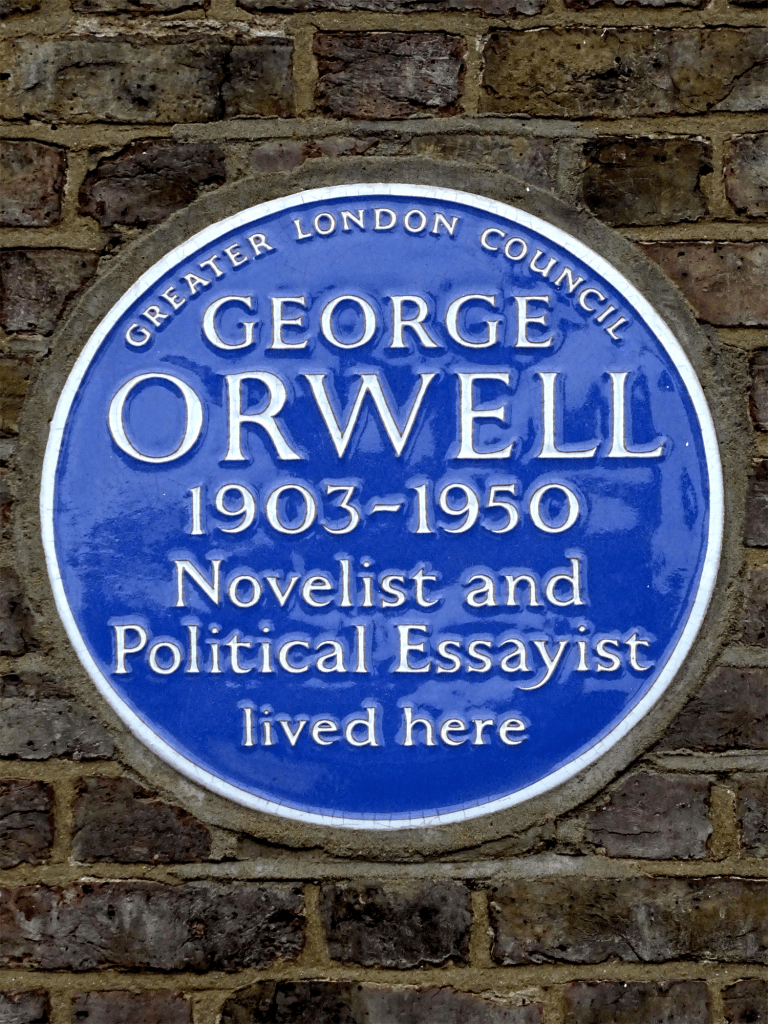

The other day, thanks to a sharp young friend from NALSAR — Ruchir Anand — I ended up reading George Orwell’s 1946 essay Politics and the English Language. But why do I say “ended up”? Well, ‘tis because I hadn’t planned on it. But once I started, it felt like a lecture – a brimming mix of bitterness and brilliance -that I could not not attend.

Among many sharp observations, Orwell said something that resonated with me. He noted how certain words or expressions — despite having no clear or consistent meaning — continue to be used, either euphemistically or dysphemistically. Talking of terms like democracy or fascism, he argues, has become so emotionally charged and overused that they are routinely used (/deployed like tools) without any precise definition. Tellingly, it is done with the tacit understanding that they don’t mean anything fixed at all. One can just toss them into any argument and come out looking holy.

Of course, now I can take a train to meet and bring Derrida to the Orwellian domain. And trust me, I am tempted to, too. For one, following Derrida’s notion of différance, one could level the same charge against the entire enterprise of language itself — that all meaning is slippery, deferred, and non-existent. And perhaps, does that convincingly so. But let’s hold back, for now and focus on a narrower category: words that are inevitably imprecise, and they are so with consensus. Yet they are used, assumed, and even unabashedly understood to convey a particular meaning, good or bad.

In Orwell’s words -“Many political words are similarly abused. The word Fascism has now no meaning except in so far as it signifies “something not desirable.” The words democracy, socialism, freedom, patriotic, realistic, justice have each of them several different meanings which cannot be reconciled with one another. In the case of a word like democracy, not only is there no agreed definition, but the attempt to make one is resisted from all sides. It is almost universally felt that when we call a country democratic we are praising it: consequently the defenders of every kind of regime claim that it is a democracy, and fear that they might have to stop using that word if it were tied down to any one meaning. Words of this kind are often used in a consciously dishonest way. That is, the person who uses them has his own private definition, but allows his hearer to think he means something quite different.“

This Orwellian insight flies in the face of intellectual property (IP) discourse, which is filled with such means that mean everything and nothing all at the same time. And if there’s one phrase that fits fine in this farrago, like a lazy politician before an election: it’s the much-bandied word: “balanced”. It goes in the same shiboleth flavours: “A balanced IP system,” “a balanced copyright framework,” “the need for balance between right holders and the public”. Pitched as self-evidently virtuous, it rarely comes with clarity.

But ask the speaker and you’ll find: it means whatever the speaker wants it to mean. After all, what is balance? For whom? When? Under what history? Hither comes a sound of silence. A loud one, my friend. The word is perhaps mightier than the magical spell — abracadabra, you say it, you’ve justified your point.

Yes, I may be biased in raising the example of “balance” — after all, it is the very subject of my PhD. (See this journal article called “Taking Copyright’s ‘Balance’ Too Seriously” where I expounded my claim in detail.) But even a brief introspection on the IP field reveals how much of its justificatory language — especially around what IP is for — is fraught with seductive yet slippery expressions.

Sample words like creativity, innovation, progress, and public interest. Lovely words, for sure. For they ring with righteous hue, sounding self-evidently good and noble. But on closer inspection, they often function — or rather, non-function — precisely as Orwell said: carrying emotional weight without definitional clarity. The speaker intentionally invokes such terms/words/expressions, thereby evading the weighty moral burden of having to exemplify the phrase they’ve uttered. Just say, “IP fosters creativity,” or “IP promotes innovation,” and voilà — the phrase earns its stand, rarely questioned, often axiomatically accepted.

The upshot is that these words are, as I like to call them, un-meant words which have managed to mean everything and nothing at once(!). And this is what makes them instrumental — and dangerously convenient —in almost any policy debate.

Of course, this isn’t unique to IP. Law and policy are full of such ‘un-meant’ words. But given how central these words/rhetorics (like the ones I flagged above) have become in global IP debates, especially endorsed through institutions like WIPO or even national IP offices, it is high time we parse the political function of such snafu signifiers. Because these signifiers — or even “noble nothings” as they are — are not just bad language. They’re politics in disguise, I posit.

So tell me, have you come across other such words in IP or law? The kind that is made to sound essential but is hollow from the inside?

Drop them in the comments. Don’t worry. I won’t misuse “transparency.” 🙂 See you in the next post.

Note: While penning this post, I was constantly recalling a solid post from Swaraj Barooah on SpicyIP called Solutionism, Social Innovation and IP.