Co-authored with Sneha Jain

In the first two posts in this series, we addressed Copyright concerns raised by Generative AI, primarily at the stage of training the LLM as well as using certain datasets. In the first post, we considered whether storing copyrightable works for training purposes is an infringing reproduction. In the second post, we analyzed whether extracting meta-information or using meta-information embedded within copyrighted works for the purposes of training the model would be infringing of any of the exclusive rights of the copyright holder, including when such content is scraped out of paywalls. We also briefly evaluated the impact of the codified exceptions and limitations under Indian Copyright law and their implications at the training stage.

In this third post, we are finally moving to the Output stage- or the downstream side of things. We address two questions here:

- Would the output generated by the AI Model, basis a query from the user, infringe the Reproduction Right of a copyright owner, whose work was inputted at the training stage?

- Would the output generated by the AI Model, basis a query from the user, infringe the Adaptation Right of a copyright owner, whose work was inputted at the training stage?

Similarity in Output and the Reproduction Right

The Reproduction Right under Section 14 of the Copyright Act protects the primary market of the original work [for derivative works like sound recordings and cinematograph films, a distinct right to exclude the making of a copy of the said work is provided. We are currently not concerned with that]. While analyzing the contours of this Reproduction Right, courts use the test of substantial similarity, to conclude whether the Defendant’s work, overall, is substituting the primary market of the owner of the Plaintiff’s work. In the seminal decision of R.G. Anand v. Deluxe Films [AIR 1978 SC 1613 [52]], the Supreme Court held that “One of the surest and the safest test to determine whether or not there has been a violation of copyright is to see if the reader, spectator or the viewer after having read or seen both the works is clearly of the opinion and gets an unmistakable impression that the subsequent work appears to be a copy of the original.” This test clarifies that unless the output generated by the model is substantially similar, i.e., unmistakably similar or a literal imitation of a previous work/ a work that is a member of the dataset, it would not infringe on the Reproduction Right of the Plaintiff.

As many have argued [see here and here], the possibility of an LLM model trained on a dataset to produce an output that is unmistakably similar or a literal imitation to any one of the inputs of the dataset, is considerably low, although it cannot be ruled out due to inherent fallibilities of LLMs as well as the potential mindset of the developer.[i] Even if the prompts inputted as queries are very specific, yet the possibility of output, that so closely resembles a single individual input that the model is trained on, is low, unless the model is specifically trained to produce regurgitations from its memorizations. Prompt injections, however, change this. Prompt injections mean inputting certain carefully designed prompts to trick the model of manipulated Gen AI into disregarding its content generation restrictions.[ii] These are often in violation of user terms and conditions. Susceptibility to such manipulation is an inherent fallibility of Generative AI and here to stay, however it requires carefully and wickedly engineered prompts, often in violation of user terms, to exploit this vulnerability of the model.

In any case, if the output produced by the model is a literal/substantial imitation of any of its training inputs, of course there would be a claim of violation of the exclusive Reproduction Right i.e., Section 14(a)(i) / (c)(i) r/w Section 51(a)(i) and Section 51 (a)(ii) of the Copyright Act. However, who will be liable for this is a different question that we shall explore in Part 4 of this series.

What we, although, need to be mindful of is that liability may only arise for violating the reproduction right if the output is substantially similar to the input. The Reproduction Right only protects against substantial similarity, which as the Supreme Court in R.G. Anand (supra) holds means similarity of the nature that will result in a situation where a person when looking at the two works as a “whole” would conclude unfair appropriation. The similarity may be in respect of certain fragments or hook parts of the original work, however, if- when looked as a “whole”, a lay person does not think it to be literal imitation or thinks of it to be a different work, the same would not be infringing. [Para 53 and 71]. In simpler terms, “substantial” has been held to mean a part of the original work which is qualitatively or quantitatively so significant that inspite of merely being a part, it makes the whole of the two works seem similar, thus reducing the differences to plain noise, and giving an impression of it being a colorable imitation.

As per a couple of interim orders of the Bombay High Court in Ram Sampath v. Rajesh Roshan and ors. [2008 SCC OnLine Bom 1722] and Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation v. Sohail Maklai Entertainment Pvt. Ltd. and Anr. [2010 SCC OnLine Bom 1577], copying of even fragments of works, which may be “hooks” would be infringing, terming the test to be where an illiterate person thinks that “Hay! I have heard this tune before”, i.e., is reminded of the former tune.

The correctness of the legal position of these interim orders, when analyzed in context of the binding judgment in R.G. Anand (supra) is doubtful. For instance, I may think of so many songs to have sequence of notes that are similar to the basic hook note sequence of “Hey Jude” by The Beatles, embedded within their work. However, that would not mean that the analysis of similarity would have to be divorced of the context of the work looked at/compared as a “whole”. Such a test ignores the material context surrounding the fragment, and its contribution to the originality of the whole work over which copyright rests in the first place. Such an inward fragmentation approach to the Reproduction Right, expanding exclusivity to include even fragments or elements of the work divorced from its context, is arguably outside the scope and purport of the right. In other words, the “substantially similar” test mandates a holistic comparison of the works, as against comparison of certain elements (which may be qualitatively significant) of the work, divorced from its overall context.

In any case, for our purposes, it is noteworthy that Courts may hold reproduction of notable or qualitatively essential fragments of works at the output stage to be infringing relying upon the aforementioned interim orders.

Importantly, however, the Reproduction Right does not extend to the the basic themes of the work, style of the author, or the generic storyline of the work, but only the expression as a whole. The former constitute ideas and are not protectable.

The Adaptation Right

When a claim under the Reproduction Right fails, the focus shifts towards the “Adaptation Right” which, due to its literal phrasing, has a seemingly larger scope, encompassing uses of works which even alter or re-arrange the original so long that it retains the core of the primary expression. The connotation, as commonly understood, is similar to extending the primary market of the copyright owner to works that are based on a previous work [creation of a secondary market]. However, arguably this common understanding is at odds with the purpose of the Adaptation Right.

In fact, the Adaptation Right for original works (the said right is not available for derivative works like sound recordings and cinematograph films), as originally conceived under the Indian Copyright Act, limited the secondary market of the Copyright owner to conversions, translations, abridgements and transcriptions. [Section 2(a)(i)-(iv) of the Copyright Act]. What this arguably indicates is that the focus of the Adaptation Right was on the same expression (originally produced by the owner of the primary work), communicated in a different format / medium. In other words, originally conceived, the Copyright Act created a secondary market for the owner of a work but limited its scope to representations of the identical work in a secondary format. However, with the Amendment to the Copyright Act in 1994, the scope of the Adaptation Right was expanded to include any use involving re-arrangement or alteration [Section 2(a)(v)]. This was, according to the Notes to Clauses to the Amending Bill, added to bring the Act more in consonance with the Berne Convention, which provides in Article 12, exclusive rights over rearrangements and alterations.

However, an expansive reading of alteration has potential to swallow all transformative depictions, using elements of prior works, including meta-information embedded within them. This has, in fact, been clarified by the Division Bench of the Calcutta High Court in Barbara Taylor Bradford and Anr. v. Sahara Media Entertainment Ltd. and Ors [2004 (28) PTC 474 (Cal)], which consciously restricted the scope of the word “alter” to minor alterations, which do not transform the core purpose and character, as well and meaning and message conveyed by the overall work. Holding against full internalization of value even through use of fragments of a work, the Division Bench of the Calcutta High Court held that a purposive interpretation of the definition of Adaptation under Section 2(a) of the Copyright Act, clearly points towards a limited reading of “alter” to only be used in cases of works which cannot ideally be represented in a different medium- for instance computer programmes, as well as to reduce its purport to slight or minor changes which do not transform the work. The Calcutta High Court held:

“125. This argument of Mr. Sen deserves full attention. Rearrangement not being very much in issue in our case, we put to Mr. Sen the question what the meaning of the word “alteration” in this sub-section was. Did it mean mutation or transformation, and did it include such extreme changes also ?

126. Mr. Sen could not maintain any argument of this extreme form, that by introduction of this amendment, the Copyright Law has been so altered in India, that if a literary work is taken by somebody other than the author, and it is so changed and muted as to make it transformed, and a different work altogether, even then copyright would be infringed. Such an interpretation of this sub-section would make nonsense of the Indian Copyright Law. A totally changed thing can never be termed a copy of the original thing. How can copyright affect the right in something, which is not related to the protected work’s copying or reproduction at all ? Pursuant to our queries, Mr. Sen referred us to several Dictionaries. Dictionaries are the last resort of Judges who either find it difficult to give a meaning to a particular word, or, having deal with all the other principles and authorities, and just for the sake of completeness, refer to these voluminous and useful works.

127. On the basis of what we saw from the Dictionaries, and on the basis of common knowledge of the English language, it appears to us that the word “altered” is capable both of meaning slight changes and of meaning extreme changes.

….

131. In our opinion, the large change meaning cannot be ascribed to the word “alter” in Section 2(a)(v) of the Copyright Act, 1957, because it renders the interpretation absurd. Minor change, slight change, not making the original something beyond recognizable possibilities, changes in some of the details, this would be the meaning that would fit the word alter in Sub-section (v). In our opinion this sub-section might have a very good bearing when applied to copyrights of computer programmes and databases, but in relation to literary works, the sub-section does not bring in any very great changes in the law; one can at best say that the subsection would make it slightly, we repeat only slightly, easier for an author or an authoress to establish infringement, after its introduction, than it would have been before the introduction. It is often misleading to speak of percentages in legal matter, but the difference made by introduction of this sub-section for literary works is the sort of difference that exists between two mathematics answer papers, one of which gets, say, 46% and the other 52$. There is no reason why we have mentioned these two figures but if this clears the understanding even a little bit, then the illustration would have well served its purpose. In our opinion, the view that we take of the strength of the prima facie case of the plaintiffs, cannot be altered (meaning radically changed) by the introduction of this subsection only, and by reason merely of the presence of this single new sub-section.”

Even in UK, which is a fully Berne compliant country, adaptations are limited to medium/format changes, and alterations/rearrangements are only considered adaptations for computer programmes.[iii]

This interpretation is arguably in line with the decision of the Division Bench of the Delhi High Court in University of Cambridge v. BD Bhandari [2011 SCC OnLine Del 3216], which protects uses of works for “transformative purposes” or a “transformative character”. It ensures that the Adaptation Right, Reproduction Right as well as the transformative use exemption (3 distinct concepts within the same Act), harmoniously co-exist without impinging on either of their scope and purposes.

In light of the above, output produced by Generative AI models which are merely based on inputted datasets/works, would arguably not ipso facto be hit by the Adaptation Right, unless the output is essentially the same/substantially similar work in a different format of expression, or the output even in the same format merely includes trivial/minor variations which do not rise to the level of transforming the character of the work.

It may be noteworthy to mention that no analogy can be drawn to the “based on” framing of the Derivative Works Right in the United States because of two reasons:

- The Derivative Work Right in the United States self-proclaimedly is beyond Berne, following the logic of expanding exclusionary rights to all channels which expose even fragments of the primary work to the public. The US had a similar restricted framing in its 1909 Copyright Act, however it rejected the same and rather adopted a broader and more open-ended Derivative Works right in its 1970 Statute. As Prof. Pamela Samuelson documents,[iv] at least one publisher wanted the Derivative Right to cover more than Berne-Style adaptations as an “adaptation” oriented framing cut down the intention of excludabilities covering any work “based upon” a preexisting original work. India refuses this and is fully Berne compliant.

- Even in the US, as many scholars argue, the scope of the Derivative Right is restricted to transformed forms/formats and not all kinds of alterations or outputs based on a previous work, which impinge on the transformative use doctrine within its Fair Use doctrine.[v] Moreover, the Ninth Circuit in the United States has rejected the “based on” understanding of this right, and has reiterated that to constitute a derivative work, the “infringing work must incorporate in some form a portion of the copyrighted work,….[and] must be substantially similar to the copyrighted work.” [Vault Corp v. Quaid Software Ltd., 847 F.2d 255, 267 (5th Cir. 1988), quoting Litchfield v. Spielberg, 736 F.2d 255, 267 (9th Cir. 1984)].

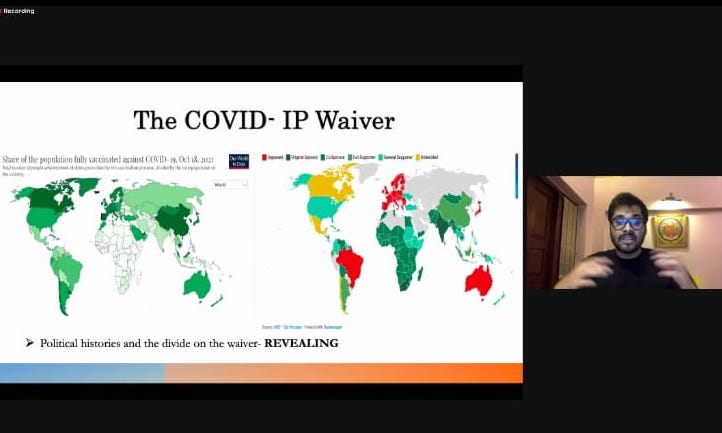

Finally, as an epilogue to this piece, we would like to suggest that when thinking about copyright liability of allegedly infringing outputs, one needs to be mindful of the fact that even if the act of creating substitutes of human creativity, based on datasets that are exemplars of human creativity, seem “harmful” from the point of view of the copyright owner, more often that not, they are not copyright’s concern, unless the expression is actually copied. Independent creation that is not copied is infact fostered in copyright law as against constrained even when it uses the meta-embedded information within previously produced expressions. It increases competition, which is desirable in a cultural and semiotic society. Hindering the same, using the tool of copyright law, basing it on an argument of existential crises for creative industries [an argument non-existent in copyright jurisprudence] is undesirable. We rather need to look towards more social solutions of providing external opportunities for creative industries to not lose out in competition to AI, by using it as a tool, or by political changes like social basic income, as against shrugging Gen AI models which significantly enrich our cultural realm.

[i] Ido Kilovaty, “Hacking Generative AI”, 58 LOY. L.A. L. REV __ (forthcoming), available at <https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4788909>. See also, Katherine Lee, James Grimmelmann, A. Feder Cooper, “Talkin’ Bout AI Generation: Copyright and the Generative AI Supply Chain”, Journal of the Copyright Society of the United States (forthcoming 2024) < https://arxiv.org/pdf/2309.08133>.

[ii] Yangyi Chen, “Exploring the Universal Vulnerability of Prompt based learning paradigm”, arXiv:2204.05239v1 [cs.CL] 11 Apr 2022, available at <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/362254964_Exploring_the_Universal_Vulnerability_of_Prompt-based_Learning_Paradigm>; See also, Ido Kilovaty, “Hacking Generative AI”, 58 LOY. L.A. L. REV __ (forthcoming), available at <https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4788909>.

[iii] Section 21 of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

[iv] Pamela Samuelson, The Quest for a Sound Conception of Copyright’s Derivative Work Right, 101 GEO. L.J. 1505,1512-1513 (2013).

[v] Talha Syed & Oren Bracha, Copyright Rebooted, Presentation at the 2022 Stanford University Law School Intellectual Property Scholars Conference (Aug. 12, 2022) (unpublished manuscript) (on file with author), See also: Akshat Agrawal, Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith: A misnomer of a debate, PhilIPnPolicy Blog [22nd October 2022], available at < https://philipandpolicy.wordpress.com/2022/10/22/andy-warhol-foundation-v-goldsmith-a-misnomer-of-a-debate/>.