Namaskar readers from PhilLIP,

I’m Lokesh Vyas— a blogger who, along with my dear friend Akshat, started this blog a few years ago. We called it PhilLIP — short for Philosophy, Law, and Intellectual Property. Our aim was (and still is) to reflect on IP issues, or broadly, the problems of information regulation, especially from a theoretical or philosophical perspective — to theorise or philosophise IP, if you will.

While Akshat, being the Akshat — ever-curious, ever-enthusiastic about all things IP — found time to write, I, on the other hand, let procrastination (and an overloaded schedule) get the better of my writing ambitions. But, as the wise say, better late than never. And here I am.

In the meantime, I’ve been writing occasionally for SpicyIP, IPRMENTLAW, and academic journals (see my SSRN page). However, due to my PhD life, I have many thoughts and ideas (just “musings”) — which I believe are worth developing — that don’t always find their way into thoroughly researched pieces. That’s what I hope PhilLIP can still offer space for.

Going forward, I’ll use this blog to share: short musings and critical notes, historical tidbits or archival insights I stumble upon in my research, and perhaps even unfinished thoughts that deserve conversation, if not yet conclusions. We can, I hope, keep the conversations going.

Without further ado, here’s my first post, not exactly on IP but on “the politics of academic writing”. These are working notes from a panel I recently organised at Sciences Po, Paris.

I’ve been mulling over the politics of academic writing for a while now, thanks to my friend and co-author on this project, Aditya Gupta—an enterprising Indian scholar with a sharp eye for these things. We named this project “Namaskari Scholar”—a scholar who treats academic writing as performance while resisting and unpacking its symbolic violence. The central idea behind Namaskari Scholar is simple: in academia, it’s not just what you write that matters, but how you write it. And the “how” is often shaped by assumptions that determine whose voices are considered legitimate, and whose are dismissed as noise, excess, or emotion.

This broader reflection led me to organise a panel at Sciences Po, Paris — my current academic home — as part of our intensive doctoral week. I’m grateful to my kind and encouraging professor, Jean d’Aspremont, who first suggested that I put together something for the event. Last week, we successfully hosted the panel, featuring three truly outstanding speakers: Professor Surabhi Ranganathan, Rashmi Dharia, and Professor Jean d’Aspremont himself.

How It Began

The idea first occurred to me while I was reading “The Geopolitics of Academic Writing” by Professor Suresh Canagarajah. He argues — and persuasively so— that academic writing isn’t neutral. It adheres to Western conventions and expectations, often enforced through citation norms, peer review standards, and publishing structures that disproportionately favour certain voices, styles, and regions.

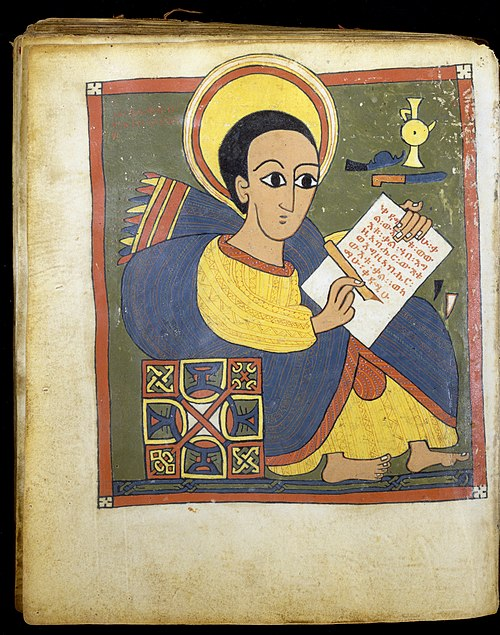

One example that stayed with me: In many South Asian traditions, texts often begin with an invocation or blessing. A Hindu might start with “Shri Ganeshaya Namaha,” a Muslim with “Bismillah ir-Rahman ir-Rahim.” Even in older European academic writing, scholars would begin with “Dear Editors” or “Dear Readers.” These gestures — forms of address that locate the scholar in a social or spiritual world — are rarely found or accepted in today’s academic writing, which prefers the impersonal, third-person, “neutral” voice.

That point resonated deeply. In my own experience, I’ve often been told that I write “too personally” — mainly because I blog and reflect in ways that aren’t always seen as “academic.” That made me pause. Why is the personal voice seen as less rigorous? Why are different styles of expression seen as less valid?

Of course, academic writing is just one of many issues in academia. Regarding the politics of academic writing, two key issues warrant deliberation:

First, there seems to be an unspoken capital—a kind of cultural and epistemic currency—that one must possess to succeed in academia. Simply put, to be an academic, one must have what Bourdieu would call capital: the right style, tone, cadence, and codes, or, in the interest of brevity, the right performance. Those who perform academic writing can gain access and authority; those who don’t are often sidelined or branded as non-academic, radical, deviant, or unreadable. Seen this way, academic writing doesn’t just express thought—it defines what counts as thought, and who counts as a thinker. It controls discourse—the way of thinking and talking about academia.

This panel began from the premise that academic writing is not neutral. It disciplines. It subjectivises. It polices. It silences. It shapes who can speak, in what form, and with what consequence. Drawing on lived experiences and theory, the panel explored how academic writing is taught, performed, and policed through various mechanisms, including pedagogy, peer review, citation norms, and editorial gatekeeping.

Now, to be clear: I’m not arguing that we abandon structure or start writing purely or only in slang. Resistance can take many forms. In fact, new forms of writing are being accepted in academia. I am advocating for more diverse modes of academic expression — more openness to multiple voices, idioms, and epistemic styles. Because when we privilege only one kind of voice, we don’t just limit access; we reproduce exclusion, silently but surely. (See generally, Melonie Fullick‘s potent post on politics of knowledge and academic writing. Check its comment sections!)

So the question is: should we continue to privilege a narrow, often US- or UK-centred idea of what “good” academic writing looks like? Or can we imagine more inclusive, plural modes of scholarly expression? Because if we don’t, then it’s not really about what you say—it’s also about how you say it. And only when you say it in the “right” way does your thought get recognised as a legitimate thought. Otherwise, it’s just dismissed as noise, emotion, or cultural excess.

This conversation is even more urgent today, in the age of AI. Generative AI has already begun to reshape how we write and think. However, if AI is primarily trained on dominant academic styles—such as objective, third-person, and de-personalised—then future writing produced with its help will likely reproduce the same epistemic hierarchies. That’s why I believe we must reflect on these questions now.

In sum, to write differently — with subjectivity, feeling, emotion — is not to write less seriously. It is to take writing seriously enough to ask: Who is it for? What does it silence? And what could it become if we did it otherwise? Here, the figure of Namaskari Scholar comes— the one who bows in greeting, writes with intention, and refuses to flatten themselves just to fit the page.

More soon. À bientôt !

— LV