In Dilution Redefined for the Year 2002, the author Jerre B. Swann, Sr., defends the doctrine of Dilution in Trademark law- which protects marks with a reputation across all kinds of products i.e., irrespective of whether the infringer uses the reputed mark in the context of distinct product classes or not- by invoking marketing theories of clarity, clutter, and cognition. His main claims are, first, based on the personhood relation of a proprietor to a mark, condemning any unauthorized use as leeching, given reputation in a mark is like the face of a person- something which is inherently theirs and no one else’s. Second, by shifting focus on the consumer, he argues that distinct and reputable marks enter the consumer’s mind and make them singularly think of a particular thing- the referent that is sold. According to him, out-of-context use of the said mark by someone else who is not its first appropriator erodes the singularity associated with the mark in respect of the information sought to be conveyed. He uses this to argue that singularity retains immediate cognitive responses, and the more number of propositions that come to be related to a signifier or its concept, the lesser the possibility of an immediate cognitive response to the mark. Although the author acknowledges that initially there was criticism of this approach as it seemed to overlap with Copyright law, he shrugs it off by arguing that the ultimate goal of Dilution is to protect mental informational associations/ what he calls “sensations”, of consumers in relation to a brand and its reputation, blindsiding its property-esque characteristics, and enmeshing it with the purpose of protecting consumers from sensation-al, deception.

I criticize the arguments of the author, first, from a semiotic perspective, and second, from the perspective of purposive goals of Trademark law and inherent limits that its doctrine sets on its property-esque character- limits that are often evaporated by the Dilution or the Well-Known mark doctrine, making it incompatible with free expression. I also argue free riding to be a misconceived premise- as what the author refers to as free riding only represents a positive externality that does not cause any harm to the owner of the mark in its context.

First, the author argues that modern Trademarks “convey, among a multitude of other messages- personality, purpose, performance, preparation, properties, price, position, and panache.” The author also postulates his five-step Dilution formula, arguing that the owner of a unique and reputed marketing symbol should be entitled to prevent impairment of its communicative clarity of association by anyone else using a similar symbol. The author refers to this as singularity, arguing the signal value of a mark- word or symbol- to cognitively be linked to its singular association.

What the author misses is the emptiness of these claims when divorced from the particular product i.e., the particular context in which the mark or symbol is specifically being communicated. The singularity of association is expressly rejected not only within the legal substance of the Trademark doctrine but also in social semiotic theory developed by Ferdinand de Saussure as interpreted by Talha Syed and applied in his critique of legal formalism.

Trademark law, itself, rejects this theory of symbols having only singular meanings/associations across all products. The use of the word or symbol “apple” as an apple (as we know) does not erode the possibility of someone using Apple in the context of electronics. If I go to a grocery store and ask for an apple, the store coordinator would not give me an Apple device, and if I go to an electronic store and ask for an apple, the store coordinator would not bring me an apple to eat. Importantly, if I go to an automobile store and ask for an apple, the store owner would be very confused and would not know what to do. Allowing this to happen, Trademark law implicitly rejects this notion of singularity. Further, Trademark law’s prevention of the use of descriptive terms (i.e., symbols already associated with certain products in language) is only applicable in respect of the product it is generally supposed to describe. It does not extend to marketers of other products, lest Apple would never have been allowed to Trademark its word in the context of electronic devices. This shows how Trademark policy, implicitly, dismisses any notion of singularity in the context of a word or its use as a mark.

In any case, when divorced from the context of use, words have no fixed meanings. The context in fact constitutes or generates the associated meaning. Words are merely labels for concepts that have a relational purpose in a particular context. Talha Syed, while interpreting Saussure shows this using the instance of the “Stop” sign, where he argues that neither the signifier nor the sign matters. It is the signified in a relevant context, that evokes association or helps us make sense of what is being communicated. When a “Stop” sign appears for the pedestrian, it does not mean that the pedestrian is supposed to literally stop. It signifies or communicates a concept that is understood in a particular context – the context of the pedestrian walking on a road where cars also move- the concept that- hey pedestrian! you are now advised to see around you for traffic signals and accordingly cross the road. Thus, divorced from context, words have no specific meaning that is signified and are empty labels with no communicative function. Trademark use, essentially, involves similar functional use- i.e., communicating to the user- the particular source of a particular product that is present around other similar products. It thus generates continuous conceptual association of sources in the minds of the consumer in respect of those products, or a family of similar products. There is no presumptuous communicative association that automatically arises across multiple kinds of products. The same word/symbol could signify a different concept forged in a different context – i.e., in relation to a completely different product. This is exactly the reason why cross-class, or cross-product usage of similar marks is allowed in Trademark law around the world.

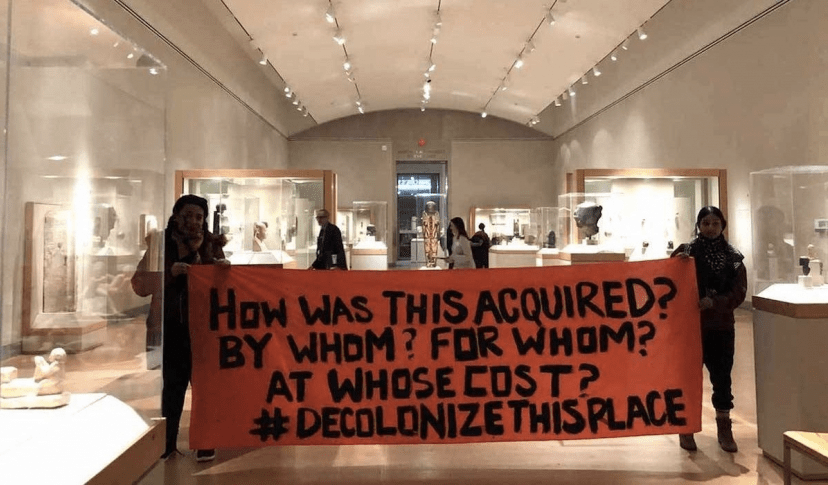

The context in which communicative association is curated outdoes this logic of singularity and lays the Dilution doctrine at odds with the other features of Trademark law. Trademark law provides rights to exclude to those who coin distinctive associational signifiers to communicate to the consumer that it is their product, however, while doing this- these signifiers automatically become a part of the discursive sphere- vulnerable to be forged in an alternate context. Trademark law allows these exclusions if uses are in the same communicative context – that is in the context of the same product, or similar kinds of products (what is often referred to as the same class of products through the NICE classification system). However, as shown above, if used in a different context, distinct meanings of the same words could be forged to communicate or signify a distinct concept or association. The Dilution doctrine however changes this and extends protection to cross-class/cross-product usage if the mark is reputed, denuding the ability to communicate or forge a separate association using a word/symbol/mark. A criticism of this approach comes back to the apple example- which shows how human minds gradually associate a separate message with a word/symbol in a distinct context. When Apple would have started using the word in the context of electronics, such an association might have initially been awkward. However, the alternate semiotic message to be conveyed gets gradually fixated in a distinct context through constant continuous use. No one who goes to an Apple store or a grocery store, anymore, misassociates these two products which are linguistically communicated using the same word/symbol/signifier. Dilution doctrine erodes this gradual possibility of a word having multiple communicative associations, and misrepresents it by creating the delusion of singularity – something at odds with free speech and communication. Why? Exactly for the reason that provoked skepticism when the Dilution doctrine was first adopted- extending copyright-like rights to exclude over words/symbols/signifiers, to appropriate revenues from every channel that would expose coined terms to the public. And why Trademark law? One of the reasons is the perpetual nature of Trademark excludability.

Trademark law does not aim to incentivize/enable the production of new words. Copyright law, which focuses on the enablement of creative expressions, does not extend rights to exclude to words by themselves considering them building blocks of expression. How do we then justify the argument of the author where he says- for Dilution a symbol need not just be distinctive in respect of the product, but also vis-à-vis other marks? This theory- endorsing competitive edge for coining distinctive symbols- would only seem justifiable if the social interest that the law sought to protect was the enablement of the production of distinctive marks or words. On the contrary, the only reason why the law seems to provide rights to exclude to owners of distinctive marks is to ensure consumers have constant associations of words with certain products in the context of their use. Extending them to all kinds of possible products, in respect of which the mark is not even being used, would be to curb the use of language, and exclude the use of words or signifiers from representing or communicating alternate ideas in alternate contexts- something which Copyright law expressly promotes by rejecting rights to exclude over words. Isn’t Dilution in Trademark law, and Copyright law thus, in fact, at odds, as against merely overlapping?

In any case, treating Trademark excludability as property rights over coined words would extend the kind of protection which Article I Cl. 8 of the US Constitution envisions. However, the perpetuity of Trademark excludability runs at odds with the limiting clause of Art. I Cl. 8. Even if Trademark law is considered a part of this clause (although the same is expressly rejected in The Trademark Cases), limiting the excludability of the coined word to use in the context of the product it represents is this inherent limit– to ensure it does not impede communicative interests associated with signifiers. Similarly, genericide is an inherent limit on the time of protection to a mark, as the interest sought to be protected is consumer confusion/deception (and not enablement or creation of new words). The Abercrombie spectrum further represents this- a mark that is distinctive gets stronger and thus longer protection, in the sense, it’s stronger only because the possibility of its generic association is least, to begin with until it travels and becomes integrated within general linguistic use out of the context in which it was protected. However, once a mark attains a substantial reputation for Dilution to kick in (i) it is already substantially integrated within the language for expressive concerns to begin, and (ii) a consumer being confused by someone using it – is less significant a consequence for the proprietor as against a consumer being voluntarily diverted.

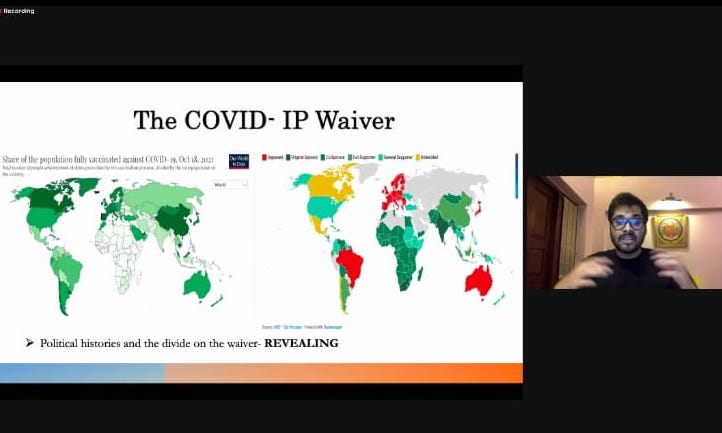

This brings me to the last leg of the critique- free riding, which focuses on diversion by use of the mark, as against confusion. A justification for protection against free-riding is that it creates a negative externality for the Trademark owner by derailing a potential source of income or the possibility of an expanded market. However, a mere possibility of expansion of the market or a potential association of a reputed mark, without creating any confusion, cannot, in my opinion, be a legitimate interest when competed with the interest of using reputed and popular words/symbols that have communicative or semiotic functions. The same is not a viable interest (especially in the case of a reputed mark that already has a significant source of income) to erode semiotic functions of the integrated word/symbol and limit it to a unitary meaning in all contexts. From Hugo Grotius (an early natural law theorist) to Mark Lemley (a recent law and economics theorist), all acknowledge that an interest to use things that are otherwise excluded, without demeaning any legitimate interest of the excluder, is a positive externality and is socially permissible. Thus, in my opinion, the use of Louis Vuitton to sell groceries, although awkward in the beginning, would in no way harm the bag seller in the current time (they may argue that the potential to expand is hurt, but Trademark law should only concern with actual use, not probable use) and would promote a legitimate speech interest of generating alternate associations and forging alternate meanings.

Taking this argument further to the “Rolex” example in Trademarks Unplugged by Alex Kozinski, any seller of the premium watch- Rolex would not be legitimately hurt by a so-called counterfeiter selling cheap watches with the label Rolex on the street, as neither would a consumer of the fake be a potential market of the initial owner nor would there be any associational loss (as no reasonable Rolex customer would be confused or would associate it with the rich person’s Rolex).

The only loss to the proprietor of the reputed mark here is what I refer to as the possible propertarian moral loss. To elaborate, the only interests of the proprietor that are hurt are- (i) third-party associational interests (but that is not a consumer), and (ii) most importantly in the panache of the mark’s associated product, generated by keeping supply low and prices high. However, whether this is a legitimate interest, is debatable. In my opinion, an interest that enhances societal hierarchies inconsiderate of distributive capabilities is not a legitimate interest when competing with the communicative interest of using the word Rolex in a way that does not confuse or deceive consumers (not third parties) about the origin of the associated product sold under that label. An assumption that it is a natural right to protect this interest in maintaining panache through its property-esque formulation is ignorant of the limits that it faces considering competing communicative and socially re-equalizing effects of alternate concurrent use of the expression.