I did not end up posting anything on World IP Day this year. So here is a consolation for that. I am leaving all of you with a beautiful and provocative portion of the inimitable Prof. Talha Syed’s [my mentor, supervisor, and favorite law professor] speech at UC Berkeley as part of a debate (linked here). I hope you enjoy:

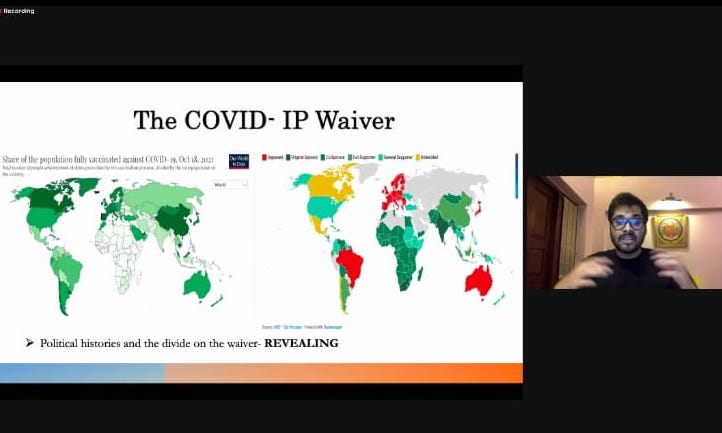

“For me, intellectual property rights—you have to begin with the basic idea that they are rights to exclude others from using a resource—information or knowledge or culture—which resource is intangible. And because it’s intangible, it’s nonrival, and because it’s nonrival, many people can use without anyone degrading anyone else’s use. So, it’s really unfortunate, unfair to restrict access on that. For me, the harm is that it restricts access to something which, once created, should be available to all because it does not derogate from anyone’s use that others share it. That’s the miracle of intangible resources.

Having said that, there are both fairness and incentive arguments for why the creator might be owed a decent return for the effort that went into creating something that’s socially valuable and that, if we don’t get that decent return, it might be that others will be discouraged from doing so, and we might get less innovation. That’s my basic, very modest framework. Access restrictions on intangible resources are a default bad idea But some way of generating those resources may be required through some legal policy to promote fairness and robust production and robust innovation.

What the ultimate principled basis of that is we could explore, and I’m happy to discuss. But it’s this mix of sort of basic ideas of wide access and fair returns that motivates my view that intellectual property rights, like some other innovation policy mechanism, should be evaluated in terms of how well they enable wide access and robust production and fair, equitable returns.

And on that, I’m not committed to intellectual property rights as being the best scheme or to how strong they should be. My own view is that current rights are, through the roof, way too strong. There’s a massive overreach. There’s a very clear, political economy story why that happens. It’s completely unfortunate, and it’s expanding to this day. And what’s happening on the internet with criminal enforcement and so forth makes it all even much worse.

So, on all that, we, I think, are not too far apart, although one could have various sort of modest disagreements. But where we disagree is sort of the foundational basis of our positions. And so, on this, I don’t have much time, so I’m going to just try to say a few things. So, Mr. Kinsella has what he claims is a sort of a libertarian, principled position based on natural rights arguments.

Now, to me, there’s a few problems with this.

First of all, it’s always puzzling to me why it’s called the libertarian position when it’s really the propertarian position. It’s not about freedom. It’s about property rights. Well, then say that. It’s a propertarian position. It’s not about an unvarnished, principled commitment to freedom. It’s about the guiding motif being something called property rights. Now, on the idea of property rights, I just want to say three things and see if I can get it in in this time.

First, of all, natural rights. I’ve never understood what people mean when they say natural rights. To me, rights are claims against others. Mr. Kinsella seems to agree. There are no rights on a desert island by yourself. Rights are claims against others. Rights are social relationships.

Now, the basis of those rights can be in various different kinds of arguments. Those are arguments. Calling them natural is just cheating. Where do they reside? They’re not your eyesight. Eyesight might be natural for some. To call something natural is a dishonest way of trying to get pre-modern warrant for a normative argument as quasi-non-normative. It is, in a word, bullshit.

There are rights, which we can respect based on reasons. We have to give reasons for those rights. When the reasons are given, they can be more or less persuasive. Calling them natural does nothing to the argument except try to convince you that it’s not a normative argument at all. It’s like a physical act. Well, there’s a chair there, don’t you know. Well, okay, good. But that doesn’t tell me about whether the chair is nice or not nice, pleasing or not pleasing, should be sat upon or not, whose chair is it, and so forth.

Those are normative arguments. Historically, until about 1700-1800s, normative arguments were couched in the language of time inmemorial, divinity, revelation, and so forth, or something called natural rights, which was a fusion of them, natural reason, according to Locke in the Second Treatise. Ultimately, natural reason is just reason, and I’m fine with arguments from reason. But putting this label “natural” on it as if it’s not any longer something human, something social, something historical, something normative, is a cheat, pure and simple. It is an attempt to deny the inescapable reality that rights are social relationships, which we have to argue about to determine which interests merit protection over which other interests.

I have no problem saying the argument should be grounded in something called right reason of the Second Treatise, but then you have to tell me what the premises and principles of that right reason are. So let me go to that second point in a moment.

On natural rights, I think the word “natural” has mental-blocking properties. The minute you say natural right, you’ve made it seem as if you’re making an argument of individuals outside of society. All rights are social, period, conceptually and institutionally. That’s just a truth. There’s nothing you can do about it except cry. But that’s what it is. All rights are social. Natural rights theorists have, for most of history, argued that natural rights can be justified in unilateral, individualist ways. Any time you get an argument that justifies someone’s rights in a unilateral, individualist way, without taking into account competing bilateral claims, it’s someone who doesn’t understand what a right is conceptually and institutionally. And that misunderstanding is facilitated by the rhetoric of natural, which has had, historically, that role. Second, “natural” also has the rhetorically loaded character of inviting you to believe that this is something you observe as an empirical claim rather than something that you argue for as a normative claim. The minute someone says, yeah, of course, all rights are social and normative and backed in normative reasons, we’re fine. Then the word “natural” plays no role. If you say, well, that’s what the word means, then my question is, well, why use the word “natural?” What does natural add except to say certain reasons do not depend on their recognition by certain contingent legislatures? Well, that I agree with. Of course, I absolutely agree that rights are not just the conventional positive legal rights that our legal system may or may not recognize. Of course, I agree we all have the right and obligation to be critical of the existing rights of a legal regime according to reflection and reason. Of course, that’s right. Anyone who doesn’t think that besides Bentham is crazy. But that’s a different view. The word “natural” doesn’t add anything.

On that second point, the idea that all rights are property rights strikes me as patently bizarre. Either it’s going to be tautologically true, because we’re going to empty the concept of property rights of any content and meaning, in which case what’s the point of the exercise? Or it’s going to be false because I don’t understand what it means to say that my interest in being able to express myself should be protected as a right against other people’s interests in not hearing what I say, and being able to violently stop myself from speaking.

Oh, well, that’s really a property interest because you’re using your vocal organs, and you own them. I don’t know what that means. I don’t know how that helps anything. I don’t know what that means except to illicitly try to reduce all human interests to the logic of the market. And that’s, to me, a very historically specific recent phenomenon, and when libertarians, or what I call propertarians, think it is somehow true from time immemorial, they’re just wrong.

There are no such arguments until very recently on the stage of history because the social form that those arguments track is very recent on the stage of history. Propertarian mindsets are the mental expression of people who live in capitalist societies. That’s fine, but that shouldn’t be then naturalized into some sort of trans-historical, human phenomenon through the gobbledygook of natural and blah, blah, blah. It just doesn’t make sense. It’s dishonest. It’s patently absurd. The argument should be made on their own terms, not with the implication of unhelpful metaphors, which try to hide the ball.

Last point. The rights of property that are being claimed as absolute and sacrosanct here are the rights in one’s body, self-ownership, and the rights in external resources based on first occupancy, fundamentally [then there’s contract and rectification]. But that’s a very strange argument, first occupancy. The first person who delimits or does something that no one else has done now has it. Locke never made that argument fully. He thought that that argument by itself was too thin a read, and he was right because, of course, by itself, that can’t be enough, just being there first.

What if you’re there first in a lot of places, and you don’t leave “enough and as good” for others? Well, there’s a problem. Locke understood that. The propertarian literature has struggled with this from the beginning. How do you deal with the in-built limit on property rights in external resources based on the “enough-and-is-good” proviso? There is a whole industry on talking about this. What does it mean to be born into an Earth that’s already been occupied and owned by everyone? What is all this about? And fundamentally, I can’t really argue against this at this time, I’m happy to argue it against it at length.

But I just want to leave you with an idea that, fundamentally, this whole mindset is a bizarre idea that humans are born fully form, self-autonomous beings at birth. They are not. They are born vulnerable, fragile, deeply dependent, social beings all the way down. Adults at some point in a market society come to resent this reality and deny it deeply by pretending something else is the case and then invent a series of fictional just-so stories which none of which have any grip for anyone who’s not already in the grip of the idea, the infantile desire to escape the reality of society and history and go back to some primordial, fictional story in which there are absolute rights, sacrosanct between self-governing sovereigns who relate to each other as pinball machines and can’t define their rights in any plausible way.

There is no such thing, period, as an absolute right because rights are social relations, and to have an absolute right would mean to have an interest protected against any other interest absolutely. And that is conceptually and institutionally not on the cards. Okay, I’ll stop.”

Hope you enjoyed it. All of this is of course “owned” by Prof. Syed. It is his “vocal organs” after all!