Namaskar Readers,

Lately, we’ve been wondering whether this blog should be called PhilIP and Policy. Although we like the name and even have a detailed note explaining why we called it that. But something changed over the period. While we intend, try, and of course want to theorise and philosophise about IP issues, we haven’t exactly been sticking too closely to that title. Especially, if you’ve read our recent posts, you’ll notice they haven’t necessarily dealt with IP law—or even theory or philosophy in any strict sense. Instead, they’ve been more like thoughtful meanderings … or musings, if you will.

Now, this doesn’t mean we’re turning the blog into an anything-goes diary—though such spaces are important and deserve far more respect in our intellectual landscape than they usually get! It’s just that our vision for this blog is a little different: to toss questions and ideas like seeds, and to see what grows therefrom. However, upon harking back, we realised that instead of strictly theorising or philosophising IP, what we’ve really been doing is musing —musing on and around IP, wandering through the many layers of knowledge production and information regulation.

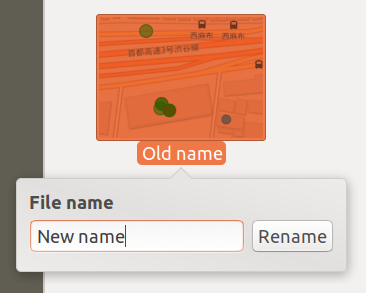

So we thought: why not rename the blog to reflect this evolving identity better? So, from here on, we’ll be calling it IP Musings. The blog name and domain name have already changed. Soon, updates in other parts will follow, and the space itself will wear this spirit more visibly. Check out the About section to learn more about who we are and what we aim to do/achieve with this space.

And now … on the name. If you didn’t already know, the word muse has a rather entrancing history, I’d say. It comes from the Old Anglo-French muser and entered writing sometime in the 14th century. As a verb, it means to become absorbed in thought; as a noun, it refers to a state of deep reflection or dreamy abstraction. Quite curious, isn’t it? So … my dear lector, isn’t “IP musing” an apposite name for this space we’re hoping to build?

That said, we still intend to anchor our reflections around IP. After all, that’s the area we’re most interested in and invested in. And perhaps (on good days), modestly qualified to comment on. With the new name, we’re giving ourselves—and officially so—the room to play and ponder. And we hope this becomes and remains a place where curiosity can cruise, ideas can breathe, questions can linger, and, more importantly, not every post needs to tie itself into a tidy academic knot. (If I can let my amateur philosopher out for a moment, I’d say this: if there truly is a journey from confusion to conclusion, what we covet here is clarity. Yes. After all, it’s the clarity of thought that lights the way—if such a journey exists at all.)

Well, that’s still not the whole story of the name. After all, just like everything else, there’s a little backstory to this title, IP Musings, too. So … a few years ago, one of us (Lokesh), along with Swaraj Barooah, had created a comic-style script series on SpicyIP called IP Reveries (which, fingers crossed, will come back soon!) It was then that we first thought of calling it IP Musings, but had to unhand the idea when we discovered a similarly titled series on Patently-O.

That said, it doesn’t appear to be in active use anymore, and more importantly, no blog or platform seems to have adopted the name. So we thought, why not reclaim it and use it for the blog? And here we are: a new name, carrying the same—perhaps even more inspirited—spirit. Because, there is something (if not everything) in a name (Sorry, Shakespeare)

Finally, before I sign off, forgive the cliché (and perhaps cheesy), but I must say it: do subscribe to the blog if you haven’t already, so you don’t miss our latest musings. And do leave your thoughts in the comments—we’d love to keep the conversation going!

With gratitude,

Lokesh and Akshat, aka The IP Musings team

(formerly PhilIP and Policy)

See you very soon in the coming posts!