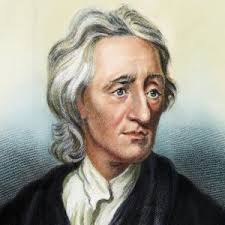

In my reading of the Second Treatise‘s property chapter, I do not find desert absent – that would overreach. Rather, I find desert claims functioning as morally appealing packaging for arguments with instrumental aims. These aims operate at two levels: (i) individual self-preservation in an emerging market society where social relations of production are driven by creation of exchange value for survival in an ever competitive environment, and (ii) social improvement to expand the overall propensity for creating exchange value – what Locke frames as God commanding labor to “improve” land “for the benefit of life,” giving it to “the Industrious and Rational,” and increasing “the common stock of mankind.” Locke writes at a moment when feudal relations are dissolving, and market dependencies are emerging as the structure governing access to subsistence. His move is articulating a theory to enclose commons in favour of someone who is expending labour or sacrifice or effort and being productive – through property rules – while packaging them in the intuitive and morally appealing language of deserving for individual desert, divine command, and natural right – “subduing or cultivating the earth, and having dominion, we see are joined together”; “God by commanding to subdue, gave authority to appropriate”.

The chain runs: God commands self-preservation → self-preservation requires continuous production → production requires continuous labour → therefore labour deserves rights → these rights are enclosures (which provide access to means of self-preservation as a matter of transaction capacity) and hence, property rights. The weight, thus, rests on self-preservation and its consequences (including “preservation of mankind” through increasing the common stock), not on effort or exertion as possessing intrinsic moral value. How self-preservation got linked to continuous production, which got linked to labour, and ultimately provided a connection to “property” which is the bounty to ensure self preservation, is not appropriately explained by Locke or Lockeans.

As the previous piece explained, self-preservation got linked to a need for continuous and self-expanding notion of production (resulting in accumulation) only in a particular epoch where through a period of transition, humans were dis-embedded from their means of subsistence, and were forced to labour and be productive for self-preservation. Productive labour is deemed “valuable” (which I shall explore in the next piece) solely because of the prevalence of this epoch, and not for any intrinsic worth that it embodies. Touting it as god’s command ignores this factual-historical reality. Moreover, Locke, no where explains, why property or enclosure is the rightly “deserved” reward for the “labour” extended, and intuitively assumes it.

When Locke writes that someone who takes “the benefit of another’s pains, which he had no right to” [§34] commits a wrong, this is a desert formulation. But what and why are these “pains”? Notice the grounding: “the penury of his condition required it of him” [§32]; “God commanded, his wants forced him to labour” [§35]. These pains are efforts compelled by preservation necessity in prevalent social relations, where such preservation (remember “safety first”?) increasingly requires productive appropriation creating exchange value. The wrong isn’t purely about respecting individual effort as such – it’s about taking what someone’s survival needs forced them to produce and they need for their own preservation. Desert is real in Locke, but it’s an instrument towards preservation as against a moral reward for effort (for any simpliciter non instrumental moral reason, as a justification with any intrinsic reasoning for itself). One deserves the fruits not because exertion is intrinsically morally worthy, but because one needs them to survive in a market society, and one’s condition (hence god’s command) forced one to produce them, apart from it adding social value to the world (to whatever extent that is). Labor matters because it produces survival-necessary mechanisms in the relevant epoch, not because mixing one’s efforts with objects carries intrinsic moral significance which is de hors any explanation.

Further. §28 states: “The Grass my Horse has bit; the Turfs my Servant has cut; and the Ore I have digg’d in any place where I have a right to them in common with others, become my Property, without the assignation or consent of any body. The labour that was mine, removing them out of that common state they were in, hath fixed my Property in them.” The servant performs the physical labor of cutting turfs. The servant’s preservation needs drove the effort. Yet the master owns the product as initial entitlement, without any contract or transfer. If property followed from personal desert, the servant should own. Locke could save appearances by invoking contractual transfer, but he doesn’t. He simply asserts master’s ownership. This makes sense if property follows from organizing productive appropriation – the master owns because he directs the productive deployment of labor (his own, his servant’s, his horse’s) toward creating exchange value. In my reading, Locke uses “one’s labor” to mean the labor one owns, not the labor one performs. Some argue this to be the naturalized reminiscent of feudalism still prevalent to an extent when Locke was writing, and not a foundation for employment relations that came much more subsequently. However, I believe, Locke assumes production relations similar to employment from the outset, embedding them in the state of nature itself. The framework concerns productive deployment, not rewarding individual exertion, simplicter. Also, I don’t think this is about slavery or coercion. Chapter IV explicitly distinguishes slavery and clarifies that men sold themselves “only to drudgery, not to slavery” [§24], with masters lacking arbitrary power. The servant relationship represents voluntary employment, yet master still owns as initial entitlement without requiring contractual transfer.

I see a functional role of labor in passages where Locke says labor “puts the difference of value on everything” [§40], “makes the far greatest part of the value of things, we enjoy in this World” [§42], and “puts the greatest part of value upon Land” [§43]. The language is consistently descriptive of function rather than prescriptive of entitlement based on effort, per se.

Locke measures this value through market exchange rather than use-value or subsistence. §43 is “the benefit mankind receives from the one in a year” measured by what it “is worth” versus what “an Indian received from it were to be valued, and sold here; at least, I may truly say, not one thousandth”. This completely orients toward creating exchange value. Even §50’s discussion of money supports this: gold and silver have value “only from the consent of Men,” yet “Labour yet makes in great part the measure” of value [§50].

Locke also says that Americans are “rich in Land, and poor in all the Comforts of Life” [§41] despite laboring, because they lack “improving it by labour.” An American “King of a large and fruitful Territory there, feeds, lodges, and is clad worse than a day Labourer in England” [§41]. Native Americans perform labor through hunting, gathering, and cultivation. They certainly exert effort. Their preservation needs certainly force labor. Yet Locke says they lack “improving” labor and therefore remain poor despite working. Americans labor and remain poor while English day-laborers – who don’t own land and work for wages – enjoy superior material conditions. In my reading then, what matters isn’t effort but productive value-creation organized within specific social relations. In this process he seems to naturalize a conception of “value” that is prevalent and relevant to his time (to the social relations constituting his mindset) as against anything else. What counts as “valuable” labor is determined by whether it’s organized within the market structures emerging in his historical moment, not by effort or productivity in any abstract sense. This is a value theory of labour: desert seems intuitive because labor creates “value,” but what constitutes “value” is itself determined by social relations preceding and constituting “value”.

This connects to a deeper problem with claiming market valuations, through rights to exclude (which are then transacted through licenses or assignments) measure what workers deserve, simpliciter. There are several problems with this approach. First, whether someone develops valuable marketable skills depends largely on morally random factors like their genetic makeup and the family and social circumstances they were born into – things they didn’t choose. Second, what the market values at any given moment reflects social factors that have little to do with moral merit, such as current consumer preferences and what labor or skills happen to be available from other workers. Third, the price something commands in the market isn’t just about a person’s abilities and what society wants; it’s also heavily influenced by various legal and institutional structures that determine how much bargaining power different people have in the marketplace – factors that have nothing to do with what someone morally deserves.

Property rights, in Locke’s text, seem instrumental to me because he says that without appropriation, resources “could be of no use, or at all beneficial to any particular Man” [§26]. “He who appropriates land to himself by his labour, does not lessen but increase the common stock of mankind… he, that incloses Land and has a greater plenty of the conveniences of life from ten acres, than he could have from an hundred left to Nature, may truly be said, to give ninety acres to Mankind” [§37]. This appeals to social consequences: increased “common stock,” “plenty,” more “conveniences of life.” He further links “subduing or cultivating the Earth” with “having Dominion” [§35], showing that he values productive improvement rather than effort per se. The “enough and as good” proviso [§§27, 33] preserves others’ productive opportunities. The common stock principle [§37] makes appropriation legitimate only when it increases general benefit.

Moreover, the spoilage limitation [§§31, 46] grounds property in actual sustenance (self-preservation needs rather than unlimited accumulation. These are preservation-based constraints.

I don’t think desert or reward or deservingness is the justification itself. I think it’s a consequence of social relations that make it compulsory, and hence convincing, to link effort or labour to some kind of reward through conferment of something valuable that can provide a link to click to access resources for needs of sustenance/ self-preservation (be it exchange value through some determined form of fair compensation that is socially provided, or self-expanding market determinant property rights (which have been more so criticized for being a circular justification)). It comes across as convincing rhetorical packaging. Just as “God commanded” or “natural reason” provides intuitive force, labor-mixing language, in a social situation where access to basics are stripped off, and labour is a way of getting access to sustenance, provides intuitive force for property rules which aim towards expanding overall production of exchange value – both for individual self-preservation in market relations and for social improvement through increasing the common stock – without doing genuine desert work in the foundational sense.

And there’s an internal tension: for Locke, the liberty that an individual possesses in his person is inalienable [§23], while the argument from self-dominion is often used to justify conceptions of legal ownership that include the right to alienate. Locke immediately uses self-ownership to create transactable property rights. Self-ownership, in my reading, thus seems to be functional – it explains the technical process by which appropriation occurs in Locke’s theory to create value that fulfills preservation needs and conveniences of life, as against having any intrinsic moral value in itself.

By framing property as arising from isolated acts of individual productive labor-mixing with nature, Locke obscures that what makes labor “productive” or “valuable” is determined by a comprehensive system of social relations – the market dependencies, competitive imperatives, employment structures that capitalism creates. The framework presents isolated individuals mixing labor with unowned nature [§§26-28], when what’s actually happening is systemic transformation of social relations that creates certain behaviors as necessary for survival. What appears as individual choice – to labor productively, to improve land, to enter employment – is actually compulsion generated by transformed property relations that render access to means of subsistence market-dependent, and hence creation of maximum exchange value imperative for survival. Locke is just theorizing a further bait – through enclosures – to make sure labour is performed as it would increase overall common stock that generates value (meaning exchange value).

Thus, the preceding post showed that labor became “valuable” and “productivity” became meaningful only because of specific historical transformation – when market-dependence made labor-for-exchange-value a survival imperative – meaning “value” itself was constituted by these new social relations, not discovered as a natural property or derived from any intrinsic moral worth related to effort or industriousness. It is relevant only because it is labour that is “productive”, and not anything else, that now helps (or is useful to) realize access to conveniences of life (as access to means of subsistence is linked to it), and the more productive one is, the better they sustain in a competitive society. This means desert claims based on labor or productivity only seem intuitively compelling because we’re already embedded in social relations where productive labour equals access to means of survival; the moral force of “labor deserves reward” derives from social conditions where not-rewarding-productive labour with value would undermine the social relations of production as source of access to basics (which feudal lords competing for now “free” peasants conceptualized by dispossessing and claiming absolute control of land (through leasehold arrangements), as explained in the preceding part).

Locke and Lockeans present the causal chain as: Labor (intrinsically valuable and morally worth) → Desert → Property rights. But the actual order, revealed by historical analysis, runs: Transformed property relations → Labor becomes “valuable” (survival-necessary) → Desert claims become intuitively appealing → Used to justify property rules and enclosures (as bounty for labour). Desert presupposes what it claims to ground. Labor doesn’t possess intrinsic value that naturally generates property rights; rather, labor became “valuable” in the relevant sense – only because the transformation explained in the preceding post made it so. When Locke argues that labor-mixing creates property rights, he’s not articulating transhistorical truth but naturalizing historically specific compulsions – theorizing as eternal what the preceding post showed was created – showing that now that productive labour is a compulsion one can make it the subject of enclosure by adverting it some “value” for purposes of exchange enabling it to be a source of realizing the means of subsistence and subsequently, conveniences of life. Are enclosures that are then transactable through exchange the only source of sustenance though?

To conclude, the moral link between labor and desert may be more historically contingent than we typically assume. In pre-capitalist contexts, labor wasn’t primarily understood through desert frameworks at all – people worked the land as embedded participants in households and communities, where “return” meant participation in a shared form of life rather than individually deserved compensation for discrete labor inputs. The desert-for-labor intuition intensifies precisely under specific conditions: when labor becomes alienated and commodified, when survival depends on selling labor time, when work is experienced as sacrifice rather than embedded activity, and when there’s constant anxiety about whether one is receiving “fair” compensation (and whether enclosure/property is the best mode of providing “fair” compensation). In other words, the moral urgency of “I deserve X for my labor” emerges from the very conditions where labor is separated from life and becomes something one must do for others who control resources. The desert framework, rather than being an intrinsic moral truth about productive activity, appears to be ideology generated by the material circumstances of capitalism itself – we must believe labor deserves return because under market dependence, that transactional logic and imputing such “value” to productive labour, is the only mechanism through which we can claim access to subsistence.

The next post will thus explore “value”.