Bonjour,

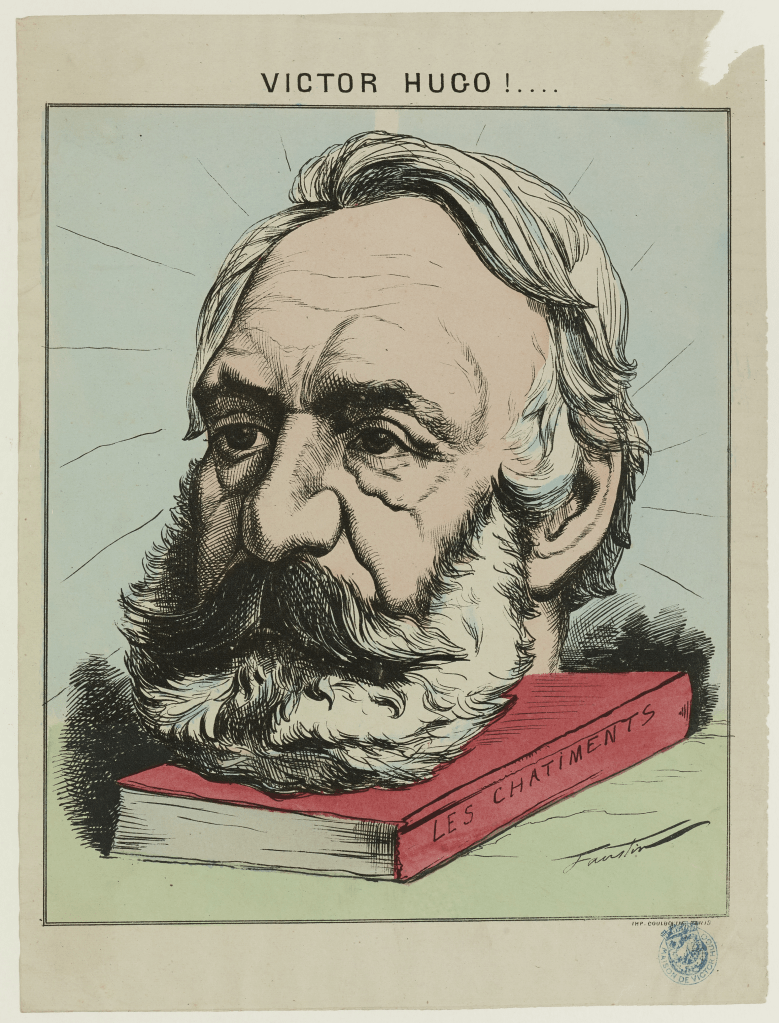

So, I was poring over the minutes of the 1878 Paris conference—the one that set the stage for the Berne Convention of 1886. And I chanced upon Victor Hugo’s first speech on 17th June 1878. He gave three speeches in total, contrary to what some believe to be two. Although I have seen some of these snippets floating around in the scholarship on the notion of public domain and public interest, etc., this time, when I read the whole thing, every word. And voilà… it hit differently. And I think it’s worth quoting in full. This post is limited to the first speech delivered on 17th June. Speech 2 is here, and Speech 3 is here.

Disclaimer – The following text is an English translation of a French original. The translation was performed using DeepL. Although I have made the best of my efforts to maintain the accuracy of the source material. I would suggest you check the original source in Pataille, J., ed. Annales de la Propriété Industrielle, Artistique et Littéraire. Vol. 25. Paris, 1880. Available through Gallica, the digital archive of the Bibliothèque nationale de France. If you don’t find the document, let me know. I will share a copy with you.

Okay, here are a few things that caught my interest –

First, I liked how Hugo defines the book and emphasises its importance to progress, using highly compelling rhetoric to make his point clear. While he discusses the public domain, it is a different kind of course—one which keeps the author’s rights perpetual, but not in a simple black-and-white manner. He says,(emphasis placed by me)

“Gentlemen, let us return to principle: respect for property. Let us affirm literary property, but at the same time, let us found the public domain. Let us go further: let us enlarge it. Let the law grant to all publishers the right to print all books after the author’s death, on the sole condition of paying to the direct heirs a very modest royalty, not exceeding in any case five or ten percent of the net profit. This very simple system, reconciling the incontestable property of the writer with the no less incontestable right of the public domain, was indicated in the commission of 1836 by the one who now addresses you; and this solution, with all its developments, may be found in the minutes of that commission, then published by the Ministry of the Interior.”

And he adds something which I found even more intriguing, given my work on the genealogy of balance discourse in international copyright law:

“Let us not forget: the principle is double. The book, as book, belongs to the author; but as thought, it belongs—to use no word too vast—to humanity. All minds have right to it. And if one of the two rights, the right of the writer or the right of the human spirit, had to be sacrificed, it would surely be the writer’s right, for the public interest is our sole preoccupation, and all, I declare, must take precedence over us. (Numerous marks of approval.)”

But mind it, it is not to be confused with the idea of balance that is thrown everywhere these days—it’s more about reconciling interest with a clear instrumental relationship with authors, right alongside that of human spirituality. In the event of a conflict, the latter would prevail.

Yes, you read him right …. if one of the two rights, that of the writer or that of the ‘human spirit’ (which seems vaguer than the notions of public interest mainly linked to limiations and exceptions these days), were to be sacrificed, it must surely be the writer’s, for the public interest is, he insists, our only true concern, and all else must yield before it. And then comes something that, to me, feels like a rhetorical sleight of hand. Hugo adds:

“But, as I have said, such a sacrifice is unnecessary. Ah, light! Light always! Light everywhere! The universal need is light. The light is in the book. Open the book wide. Let it shine, let it act. Whoever you are that would cultivate, vivify, edify, soften, appease—put books everywhere; teach, show, demonstrate; multiply schools; schools are the luminous points of civilization.”

It’s also interesting how the rhetoric of civilisation is played out here and the way the idea of literature or text is described, going to the extent of claiming that text is civilisation, underscoring a particular epistemic stand on knowledge production, which, in no way, was universal yet was enclosed like it was. (I will discuss this idea in detail in the coming days.)

Alright, that’s what piqued my curiosity the most. Below is his entire speech; see what excites or irritates you:

“Speech of Victor Hugo, President of the Congress (Solemn opening session, 17 June)

Gentlemen,

What makes this memorable year so great is that, supremely, above the rumors and clamor, imposing a majestic interruption to the astonished hostilities , it gives voice to civilization. We can say of it: it is a year that is obeyed. What it has set out to do, it is doing. It is replacing the old agenda, war, with a new agenda, progress. It is overcoming resistance. Threats are rumbling, but the union of peoples smiles. The work of the year 1878 will be indestructible and complete. Nothing is temporary. One senses in everything that is being done something definitive. This glorious year proclaims, through the Paris Exposition, the alliance of industries; through the centenary of Voltaire, the alliance of philosophies; through the congress gathered here, the alliance of literatures (Applause); a vast federation of labor in all its forms, an august edifice of human fraternity based on peasants and workers and crowned by intellectuals. (Bravo.)

Industry seeks utility, philosophy seeks truth, literature seeks beauty. Utility, truth, beauty: these are the threefold goals of all human endeavor; and the triumph of this sublime endeavor, gentlemen, is civilization among peoples and peace among men. It is to witness this triumph that you have come here from all corners of the civilized world. You are the great minds that nations love and revere, you are the famous talents, the generous voices that are listened to, the souls working for progress. You are the peacemakers. You bring here the radiance of renown. You are the ambassadors of the human spirit in this great city of Paris. Welcome. Writers, orators, poets, philosophers, thinkers, fighters, France salutes you. (Prolonged applause.)

You and we are fellow citizens of the universal city. All of us, hand in hand, affirm our unity and our alliance. Let us enter, all together, into the serene homeland, into the absolute, which is justice, into the ideal, which is truth.

It is not for personal or limited interests that you are gathered here; it is for the universal interest. What is literature? It is the setting in motion of the human spirit. What is civilization? It is the perpetual discovery made at every step by the human spirit in motion; hence the word Progress. One might say that literature and civilization are identical.

Peoples are measured by their literature. An army of two million men passes, an Iliad remains; Xerxes has the army, but lacks the epic: Xerxes fades away. Greece is small in territory but great in Aeschylus. (Movement.) Rome is but a city; but through Tacitus, Lucretius, Virgil, Horace, and Juvenal, this city fills the world. If you mention Spain, Cervantes springs to mind; if you speak of Italy, Dante rises; if you name England, Shakespeare appears. At certain moments, France can be summed up in one genius, and the splendor of Paris merges with the brilliance of Voltaire. (Repeated applause.)

Gentlemen, your mission is a lofty one. You are a kind of constituent assembly of literature. You have the authority, if not to vote on laws, at least to dictate them. Say the right things, express true ideas, and if, by some chance, you are not listened to, well, you will prove the legislation wrong.

You are going to establish a foundation, literary property. It is within the law, and you are going to introduce it into the code. For I affirm that your resolutions and your advice will be taken into account.

You are going to make it clear to legislators who would like to reduce.

You will make it clear to legislators who would like to reduce literature to a local phenomenon that literature is a universal phenomenon. Literature is the government of the human race by the human spirit. (Bravo!)

Literary property is of general utility. All old monarchical laws have denied and still deny literary property. To what end? To the end of enslavement. The writer who owns his property is The writer who owns his work is the free writer. To take away his property is to take away his independence. At least, that is the hope. Hence this singular sophism, which would be childish if it were not treacherous: thought belongs to everyone, therefore it cannot be property, so literary property does not exist. First, there is a strange confusion between the faculty of thinking, which is general, and thought, which is individual; thought is the self. Then there is confusion between thought, which is abstract, and the book, which is material. The writer’s thought, as thought, escapes any hand that would seize it; it flies from soul to soul; it has this gift and this power, virum volitare per ora; but the book is distinct from thought; as a book, it is graspable, so graspable that it is sometimes seized. ( Laughter. ) The book, a product of the printing press, belongs to industry and determines, in all its forms, a vast commercial movement; it is sold and bought; it is property, value created and not acquired, wealth added by the writer to the national wealth, and certainly, from all points of view, the most indisputable of properties. This inviolable property is violated by despotic governments ; they confiscate the book , hoping thus to confiscate the writer . Hence the system of royal pensions . Take everything and give back a little . Spoliation and subjugation of the writer . He is robbed , then bought . A futile effort, moreover . The writer escapes. He is made poor, but he remains free. (Applause.) Who could buy these superb consciences, Rabelais, Molière, Pascal? But the attempt is nonetheless made, and the result is grim. The monarchy is some kind of terrible suction of the vital forces of a nation; historiographers give kings the titles of fathers of the nation and fathers of letters; everything is held together in the disastrous monarchical whole; Dangeau, flatterer, notes this on one side; Vauban, stern, notes it on the other; and, for example, in what is called “the great century,” the way in which kings are fathers of the nation and fathers of letters leads to these two grim facts: the people without bread, Corneille without shoes. (Long applause.)

A dark stain on the great reign!

This is where the confiscation of property born of labor leads, whether this confiscation weighs on the people or on the writer.

Gentlemen, let us return to the principle: respect for property. Let us recognize literary property, but at the same time, let us establish the public domain. Let us go further. Let us expand it. Let the law give all publishers the right to publish all books after the death of the authors, on the sole condition of paying the direct heirs a very small royalty, which in no case exceeds five or ten percent of the net profit. This very simple system, which reconciles the writer’s indisputable property rights with the equally indisputable right of the public domain, was proposed in the 1836 commission by the person speaking to you at this moment; and this solution, with all its details, can be found in the minutes of the commission, published at the time by the Department of the Interior.

Let us not forget that there are two principles at work here. The book, as a book, belongs to the author, but as a thought, it belongs—and the word is not too broad— to humankind. All minds have a right to it. If one of the two rights, the right of the writer and the right of the human mind, were to be sacrificed, it would certainly be the right of the writer, for the public interest is our sole concern, and all, I declare, must come before us. (Numerous signs of approval.)

But, as I just said, this sacrifice is not necessary.

Ah! Light! Light always! Light everywhere! The need for everything is light. Light is in the book. Open the book wide. Let it shine, let it do its work. Whoever you are who wants to cultivate, enliven, edify, soften, appease, put books everywhere; teach, show, demonstrate; multiply schools; schools are the bright spots of civilization.

You take care of your cities, you want to be safe in your homes, you are concerned about this danger, leaving the streets dark; consider this even greater danger, leaving the human mind dark. Intelligence is like open roads; it has comings and goings, it has visitors, with good or bad intentions, it can have unfortunate passersby; a bad thought is like a thief in the night, the soul has criminals; bring light everywhere; do not leave human intelligence of those dark corners where superstition can nestle, where error can hide , where lies can lie in wait. Ignorance is twilight; evil lurks there. Think about lighting the streets, yes; but think also, think above all, about lighting the minds. (Prolonged applause.)

This requires, of course, a prodigious expenditure of light. It is to this expenditure of light that France has been devoted for three centuries. Gentlemen, allow me to say a filial word, which is in your hearts as well as in mine: nothing will prevail against France. France is of public interest. France rises above the horizon of all peoples. France rises on the horizon of all peoples. Ah! they say, it is daybreak, France is here! (Yes! Yes! Repeated bravos.)

That there may be objections to France is surprising; yet there are some; France has enemies. They are the very enemies of civilization, the enemies of books, the enemies of free thought, the enemies of emancipation, of examination, of deliverance; those who see in dogma an eternal master and in the human spirit an eternal minor. But they are wasting their efforts; the past is past, nations do not return to their vomit, blindness has an end, the dimensions of ignorance and error are limited. Accept this, men of the past, we do not fear you! Go ahead, do it, we are watching you with curiosity! Try your strength, insult ’89, depose Paris, condemn freedom of conscience, freedom of the press, freedom of the tribune, condemn civil law, condemn the revolution, condemn tolerance, condemn science, condemn progress! Do not tire! Dream, while you’re at it, of a Syllabus big enough for France and a snuffer big enough for the sun! (Unanimous acclamation. Triple round of applause.)

I do not want to end on a bitter note. Let us rise above and remain in the unchanging serenity of thought. We have begun to affirm harmony and peace; let us continue this proud and tranquil affirmation.

I have said elsewhere, and I repeat, all human wisdom can be summed up in these two words: conciliation and reconciliation; conciliation for ideas, reconciliation for men.

Gentlemen, we are here among philosophers; let us take advantage of the occasion; let us not be shy; let us speak the truth. (Smiles and signs of approval.) Here is one, a terrible one: the human race has a disease, hatred. Hatred is the mother of war; the mother is infamous, the daughter is awful.

Let us strike back at them blow for blow. Hatred for hatred! War for war! (Sensation.)

Do you know what Christ meant when he said, “Love one another”? It means universal disarmament. It means healing the human race. That is true redemption. Love one another. It is better disarms his enemy by extending his hand than by showing him his fist. This advice from Jesus is a command from God. It is good. We accept it. We are with Christ, we ourselves! The writer is with the apostle; the thinker is with the lover. (Applause.)

Ah! Let us raise the cry of civilization! No! No! No! We want neither barbarians who wage war nor savages who murder! We want neither war between peoples nor war between men. All killing is not only ferocious, but senseless. The sword is absurd and the dagger is foolish. We are the warriors of the spirit, and it is our duty to prevent the war of the flesh; our role is to always throw ourselves between the two armies. The right to life is inviolable. We do not see the crowns, if there are any, we see only the heads. To grant mercy is to make peace. When the fateful hour strikes, we ask kings to spare the lives of their people, we ask republics to spare the lives of emperors. (Applause.)

It is a beautiful day for the outcast when he begs a people for a prince, and when he tries to use, in favor of an emperor, that great right of mercy which is the right of exile.

Yes, to conciliate and reconcile. Such is our mission, we philosophers. O my brothers of science, poetry, and art, let us recognize the civilizing power of thought. With every step that humankind takes toward peace, let us feel the deep joy of truth grow within us. Let us take pride in useful work. Let us take pride in useful work. Truth is one and has no divergent rays; it has only one synonym, justice. There are not two lights, there is only one, reason. There are not two ways of being honest, sensible, and true. The ray that is in the Iliad is identical to the clarity that is in the Philosophical Dictionary. This incorruptible ray traverses the centuries with the straightness of an arrow and the purity of dawn. This ray will triumph over the night, that is to say, over antagonism and hatred. This is the great literary miracle. There is none more beautiful. Strength bewildered and stunned before justice, the arrest of war by the spirit, this, O Voltaire, is violence tamed by wisdom; this, O Homer, is Achilles seized by the hair by Minerva! (Long applause.)

And now that I am about to finish, allow me to make a wish, a wish that is not addressed to any party, but to all hearts.

Gentlemen, there is a Roman who is famous for his obsession; he said: Let us destroy Carthage! I, too, have a thought that obsesses me, and it is this: Let us destroy hatred. If the humanities have a purpose, it is this: Humaniores litteræ. Gentlemen, the best way to destroy hatred is through forgiveness. Ah! May this great year not end Ah! May this great year not end without definitive pacification, may it end in wisdom and cordiality, and after extinguishing foreign war, may it extinguish civil war. This is the deep wish of our souls. France at this hour shows the world its hospitality; may it also show its clemency. Clemency! Let us place this crown on the head of France! Every celebration is fraternal; a celebration that does not forgive someone is not a celebration. (Loud emotion. – Repeated bravos.) The logic of public joy is amnesty. Let this be the conclusion of this admirable solemnity, the World’s Fair. Reconciliation! Reconciliation! Certainly, this gathering of all the common efforts of humankind, this rendezvous of the wonders of industry and labor, this salutation of masterpieces among themselves, confronting and comparing themselves, is an august spectacle; but there is an even more august spectacle, that of the exile standing on the horizon and the homeland opening its arms! (Long acclamation; the French and foreign members of Congress surrounding the speaker on the platform come to congratulate him and shake his hand, amid repeated applause from the entire hall.)

Okay, that’s it. See you in the next post.

2 thoughts on “Speech One: Victor Hugo’s on 17 June 1878 at the Paris Conference”