Salaam Readers,

If you have read my previous blog, ‘What Makes Us Think Differently – Ideas or Their Expressions?‘, you’ll recall that I argued for the latter. Since then, I’ve sat more with the question, and something else has begun to take hold of my thinking.

This time – I’ve been pondering on thinkers like Foucault, Spivak, Judith Butler, G.N. Devy, Boaventura de Sousa Santos —those who offer what might be called “game openings” (this is Foucault’s phrase): conceptual tools, intellectual manoeuvres, or discursive devices that enable us to deconstruct/challange dominant narratives, question entrenched practices, and cerebrate the very conditions of thought. These intellectual figures have undeniably lent us powerful tools to cognise and critique structures of power and knowledge.

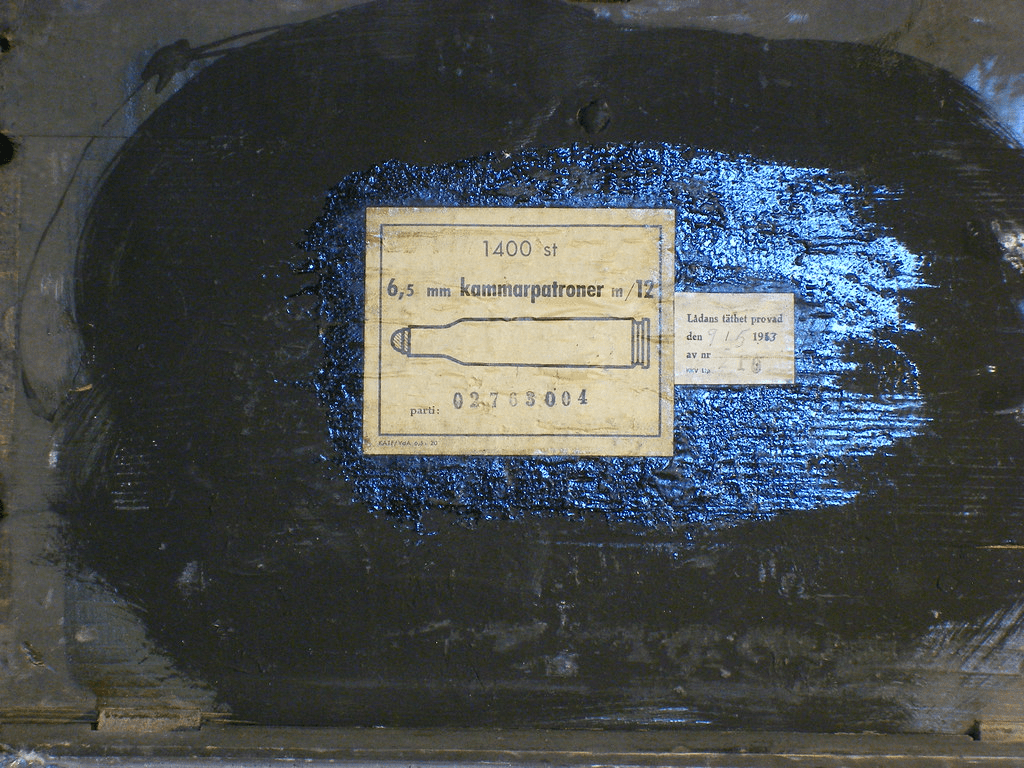

But I’ve begun to wonder: are these intellectual “ammunition” always and necessarily benign? Not everything that looks good is necessarily good, or vice versa. Perhaps it’s all just a matter of how well one can portray something as good or bad. The art of presentation. Or, maybe as Foucault says, it’s the discourse of the time that makes them good/bad at a given point.

Should we not, then, subject these very tools to scrutiny? Interrogate the kind of force they can unleash—not just in terms of theoretical disruption, but in the tangible ways they reconfigure discourse, institutions, or even our sense of what can be thought or done? A concept may open a door, yes—but it may also quietly bolt another shut.

Take, for instance, the idea of a “terrorist.” On the surface, it sounds straightforward — someone who causes terror. Simple, right? But dig a little deeper, and you’ll see there’s nothing fixed or “natural” about the term. If we go purely by the logic of causing terror, then a street dog chasing kids in a colony should qualify as much as someone on the Interpol list. But that’s clearly not how it works. There’s something else going on. Terrorists, those who are subject to punishment, surveillance, and even annihilation, derive their meanings, weight, and force from a dense web of ideas/practices/networks, including institutions, legal codes, norms, social expectations, and broader discourses.

These web don’t just describe terrorist or terrorism; they produce it. And once these meanings start circulating, they bring into being a particular kind of subject—the terrorist—who is not only a legal subject (someone who can be tried, sentenced, punished, reformed and rehabilitated) but also a social, legal, political, and economic figure. From here, the entire technology of governance can begin to operate. In IP law, this can be applied to the figure of a pirate, or infringer, which has come to mean even a person who downloads music from an unauthorised website. (See Shivam Kaushik‘s puissant piece on the topic of Piracy)

The upshot is that law doesn’t and cannot govern abstract categories. It governs concrete subjects. And to govern them, it first needs to produce them, tether them to various practices, fears, norms, and ideas. And once that tethering takes place, once the subject is stabilised within these discourse/networks, the entire game of governance gets its legitimacy, not from the truth of what terrorist ontologically is, but from the repetition and circulation of these meanings and practices.

I should clarify here that my intention here is not to comment on the ethics or equate the consequences of terrorism with anything else. Instead, I’m just demonstrating a Foucauldian game opening wherein once a framework, system, or practice—no matter how beloved or demonised—is rendered visible as a historically contingent construct, it becomes available for critique. That is, it can be interrogated, deconstructed, and even challenged — by anyone, for any reason, irrespective of original intent or projected outcomes.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that all critiques carry the same moral weight and deserve to be deployed. But it does show that once something is exposed as historically contingent — no longer natural or inevitable, bereft of the privilege of invisibility— it lands on the anvil of critique. And once it enters the “game opening” that these intellectual automations open up, wherever things can become open to interrogation, suspicion, and reframing.

And, my friend, this isn’t limited to ill ideas, problematic practices or controversial ideologies. Nah. It can apply just as much to the banal, mundane, and routine. Sample something as seemingly “natural” as our sleeping or eating schedules — something we rarely pause to probe. But suppose we put them to the anvil of critique as we do with other controversial practices/ideas (say, terrorism, homophobia, colonialism). In that case, we might uncover subtle reconfigurations shaped by industrial capitalism, electric lighting, factory timetables — all that have thus far undergirded our sense of “normal.”

Again, I must reiterate: my aim is not to dramatise or demonise the humdrum. Instead, it is to underscore that many of the intellectual ammunition, such as discourse analysis in this case, we hold dear — especially the kind of power it wields, the meanings it enables or disables — deserve interrogation. And dare I say, a deliberate one.

Put simply, once we take any such intellectual ammunition seriously to crack open something, we must simultaneously admit that any normal is just as abnormal as abnormal is to normal. The distinction lies not in truth, but in who’s holding the hammer.

So … given the historical contingency of everything around us — as these tools convincingly remind us — if all that we inhabit, invoke, or intuit, including institutions, values, and “truths” (about God and Government), is perpetually fallible and fragile, then where does that leave us? What compass do we hold, if every north is up for challenge? I don’t know, but just wondering … what do you say?

See you in the next post.