In this set of 4 posts- I shall be discussing my dilemmas from the Kacha Badam Controversy. The first post covered my thoughts on the delusion that this whole controversy has produced and the need to revamp its factual narrative. The second post covered my thoughts on the hard case that this factual narrative exposes- something I cannot really grapple with yet. The third post brainstormed thoughts on resolving this hard case. Finally, this fourth post will, in the backdrop of these three posts, discuss an amazing paper by Prof. Alpana Roy titled- “Copyright: a colonial doctrine in a post-colonial age” and how her thesis has an important role to play in figuring out/ or rather even further complicating this hard case.

PART-4

In this final post, I am discussing, Prof. Alpana Roy’s paper titled Copyright: A colonial doctrine in a post-colonial age, in the backdrop of the discussions we have had so far. I also had an opportunity of discussing this article in the Critical Interdisciplinary Perspectives to IP reading group hosted by Prof. Anjali Vats, Prof. David Jefferson, among others- which led to a lot of thoughts pushback, and questions. I shall try and put them out here This is also my expression of gratitude to all who turned up for the reading group.

Prof. Alpana Roy’s article, published in the Copyright Reporter in 26th Volume 4th Issue, in December 2008, discusses IP from a sharp post-colonial lens. It is a provocative piece of writing, to say the least.

Setting the stage, Roy clears the air on what colonialism implies and what constitutes de-colonial thinking. She clearly puts it forth that the socio-economic exploitation of the so called “periphery” or alternate, need not always be directly political or dominated by the military. It can also involve continued subordination through the exploitation of the political economy to adversely affect capabilities. She mentions the prevalence of colonial thought in law-making and how it pervades global norms, in sheer ignorance of alternate indigenous realities. This narrative somehow resembles the work of the amazing late Prof. Keith Aoki, on what he calls Neo-Colonialism, and in the context of IP states that- transnational IP system erode concepts of sovereignty and self-determination.

Putting the article in context, Roy turns to International IP Agreements and reflects on the role of these “multifaceted projects” or dominant narratives which primarily reflect/mirror particular moments in the history of Western cultural practice. She emphasizes the importance of this by projecting the dissonance of the norms in agreements like Berne, with nations outside the West. She asserts that Copyright remains a foreign concept in many cultures, and many societies take an extremely radical view on what constitutes property and can be the subject of individualistic private property. In this context, it is important to reflect on the “independent” v. “inter-dependent and inherently social conceptions of the self (the idea of a “family”)” which vary across societies – with the West bending towards the former and Asian societies towards the latter. The law, as it is in its current “global” framings, only accommodates the former, completely ignoring the latter.

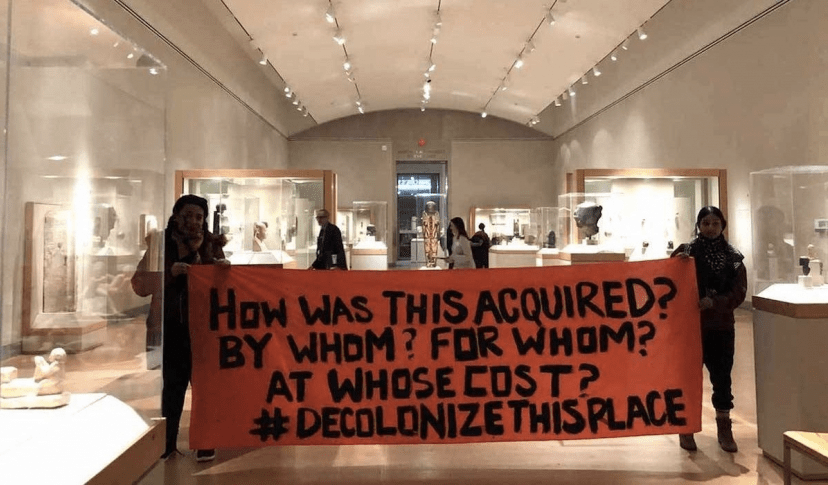

She then goes on to talk about a few of these individual dissonant features: (i) print culture (ii) the idea of piracy as against copying and sharing as a sign of respect and recognition- and mentions how such norms being globalized are nothing but a symbol of a dominant narrative used to foster a “one-way traffic around the notion of desirable culture”- consequently moving towards cultural imperialism. It is at this point where she makes her most important argument about this whole system having a far deeper impact than the earlier forms of colonialism, imperialism, or simple tourism, as it tends/attempts to alter the source of the self.

Hereon, she gets into the hard case by discussing the example of “Return to innocence”, supposedly a Taiwanese tribal song, which was appropriated out of a performance by 30 indigenous Taiwanese performers who were invited to perform across Europe by the French Ministry of Culture. A significant portion of these songs was used by a German music entrepreneur and was then also recorded by Enigma- and sold as “his copyright”, without any due accreditation or financial compensation for the use of the said song. She primarily uses this example to first- expose the political economy of cultural practice, and thereafter and most importantly, the political economy of law on culture- and who gets to enforce and who doesn’t. This is important in the context of the debate on print vs. aural culture, as well as in the context of the argument that accesses to a platform to showcase determines who gets to ‘own’. What I am concerned about, in this example, is not the appropriation, but rather the possessive claim of Enigma over this output- dispossessing many others who could have been the actual originators of the expression and should have had the ability to use, build on, or get any financial remuneration in respect thereof. It is in this context that the appropriation is important to be addressed.

Roy uses the “Return of innocence” case to contend how indigenous works fail to fulfill individualistic notions of property rights and are dispossessed from their performers through dissonant norms. She uses this to show how western law, and its hegemonic transposition is highly inappropriate, results in fictitious commodification, and continues to perpetuate the idea of the historic “other” even in law and policymaking. She aligns with Rosemary Coombe who argues that neoliberal conceptions of copyright do not accommodate cultural differences that are difficult to be formulated in terms of a commodity, and are hence difficult to encompass within the conceptual frameworks of “modernity”.

Roy also refers to oral research outputs and argues that as soon as someone publishes all the oral research output they get copyright over it- dispossessing participants and researchers who contributed and undertook research orally but did not/could not really “fix the output in the printed/published form”. On this aspect of fixation, during the discussion with the reading group, Prof. Ann Bartow put forth an interesting question as to- how do rules of evidence work in aural societies? – Historically mapping the same could be an interesting analogy to look at while discussing the irrelevance of fixation norms in non-western societies.

Roy then moves on to how these western cultural norms were exported to colonies by European colonizers as a part of the package of colonization, most prominently in the 18th and the 19th Century. She states that pirating foreign work was still prevalent in free-er countries given the US only joined the Berne until 1989 and offered little protection. To foreign authors until then. Unfortunately, those who were colonized had little say in such policy for their own capability development (I discuss this aspect of IP Gradualism in detail in my paper here).

Roy then moves to the strongest part of her paper where she argues the relevance of printing technology and entrepreneurs in respect thereof in centralizing and transplanting these western norms abroad. She talks about how printing was essential for the colonial and imperial projects of Europe as their empires could not have survived without the spread of propaganda, religious tacit, commercial documents, maps, charts, etc., among the natives. Here comes the relevance of copyright. She argues that as a form of communication- printing, unlike oral communication, has a tendency of universalizing ideas- and disseminating information through identical texts and making them truths by imposing them through “violent hierarchies” facilitated by the tool of colonialism and the Prospero complex it produces. She talks about how most of the so-called “universal truths” coincided with this enlightenment period of solitary creation and printing technology – that is basically the rise of print medium and subsequently the law of copyright. Importantly she reiterates that this exchange was not happening among “equals” but rather as an imposition in a colonial setup.

Upon political decolonization, Roy writes that there were some modest attempts at resisting western copyright by the Global South, in the context of the inability to translate and develop knowledge, however not to any structural yield. Thes prevailing norms have not only been normalized but have, through TRIPS, also been universally accepted (read: imposed), and are now a part of public international law.

Moving on to a consequential analysis of these norms, embedded with capitalism and the global political economy, Roy quotes Butalia, to argue that it is impossible to separate the world of Copyright law from the world of politics, as knowledge, culture, and access are inextricably linked with power, power is linked with money- and both of those are linked with history– something which cannot be repaired easily. In my opinion- this brings us back to the hard case and the relevance of reparative solutions to be intermingled with systemic change and to look at the same as complementary rather than as an either/or binary.

Roy finally concludes by referring to how copyright is nothing but a tool to merely further the trade and capitalist interests of western societies. However, a consequential corollary of this, which Roy misses in her analysis, is the impact of such a tool on identities and cultural estrangement- the “othering” of non-marketable culture. We might be celebrating Bhuban and his expression today, but that is only because he and many others like him, who do not fit in to this marketable system have been othered from cultural identity framing discourses and economic benefits in respect thereof, for a long, long time. As Macneil argues, we cannot subordinate the subsistence of society itself to the laws of the market, and the interest of the marketers, as it disenfranchises humans of the ability to direct the trajectories of their social institutions. We cannot, as a society afford to do this, as the same is nothing estranging identities.

To conclude these posts, the takeaway I seek to present is- the need for scholarship, research and thought on –

How to ensure that identity interests of self-determination (including remunerative concerns), especially of those who have been denied the same for long, are retained- without resorting to dissonant logics of property rights as tools of affirmative action?

Hope we have enough food for thought! Do reach out if anyone wishes to discuss any of this. I am available at 97akshatag@gmail.com

Part 1- here

Part 2- here

Part 3- here